Historic Homes: Complex Pasts, Changing Futures

Written by: Alexa Olivares

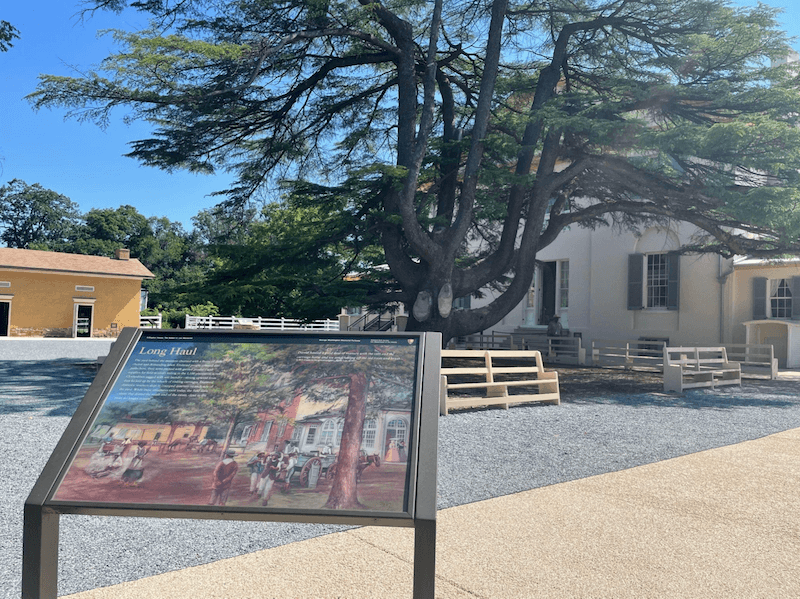

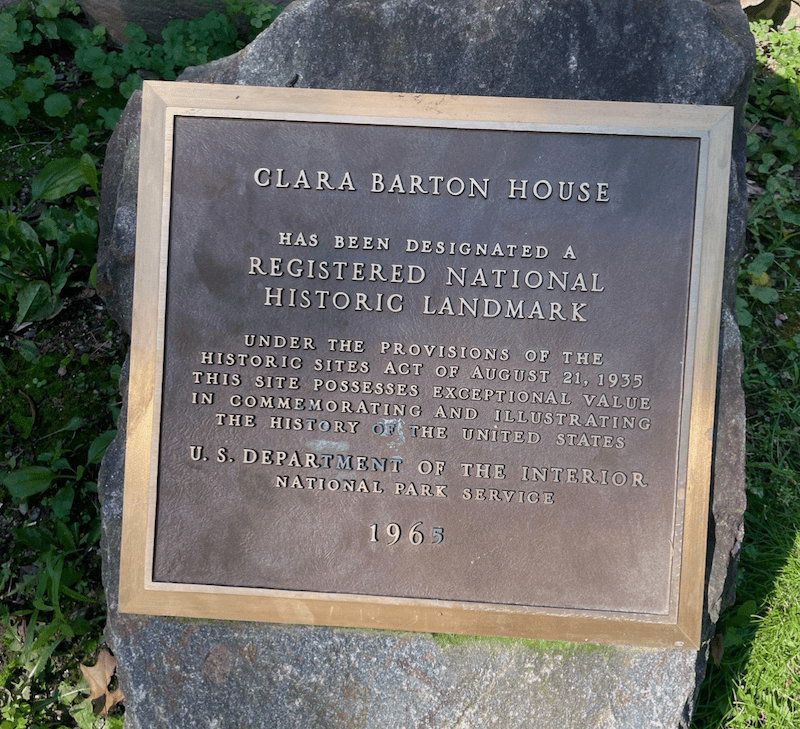

A new week at the George Washington Memorial Parkway (GWMP) was spent preparing for our visit to the Clara Barton National Historic House on June 29. There, along with several other resource management staff members, we were given an in depth tour of the house and its history. We met to discuss the future usage of the structure. Apparently the Clara Barton National Historic House, though incredibly beautiful and historically significant, receives low visitation compared with other GWMP sites like Glen Echo Park just next door. As an effort to improve this and attract more visitors Clara Barton will be partnering with Glen Echo to bring camps, art projects, music lessons, etc. to be hosted at the historic house. This process will not be an easy switch because the building must be kept not only to historic accuracy but also to modern safety and ADA standards. Similar to Great Falls park there is much to discuss in terms of concerns over accessibility versus historic integrity. Potentially adding an elevator/lift, location of said mobility aid, reconfiguration of space and storage and fixing exterior ramps are all major changes that would improve the quality of visitor usage of the house but also pose threats to the cultural landscape.

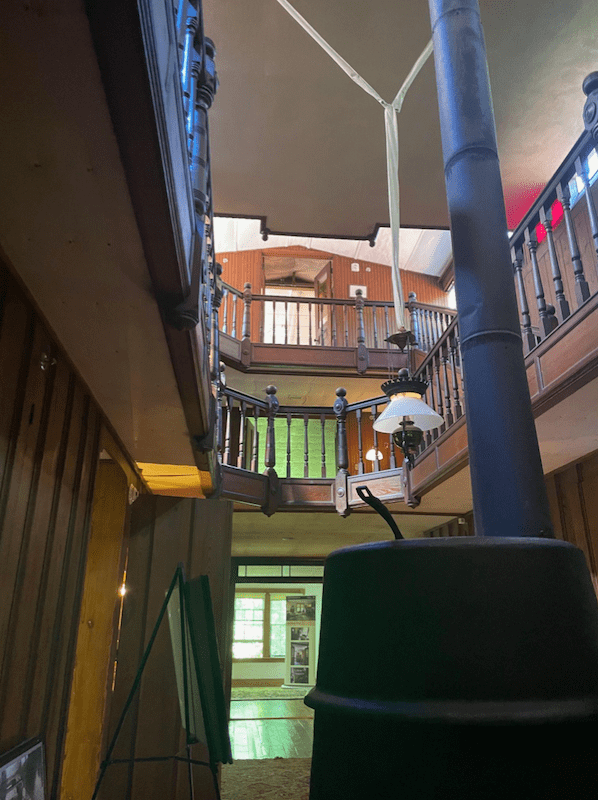

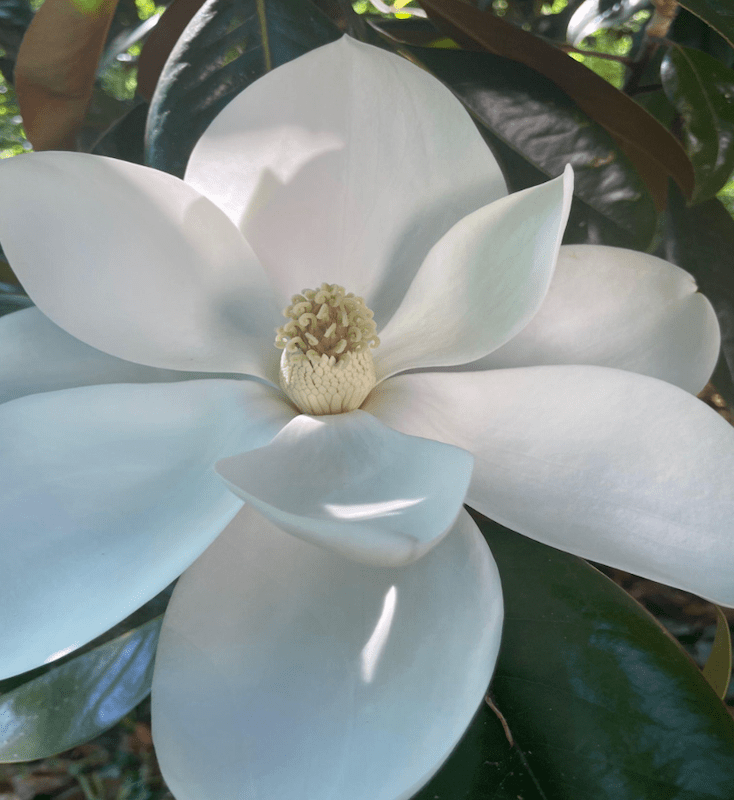

Inside the house are various reproductions, not all entirely accurate to the original structure of the house as Clara Barton herself once used it but still historically close. Clara Barton used the house as the American Red Cross headquarters where she conducted her medical humanitarian work, later it was used also as her home where she lived until her death in 1912. The interior of the home is beautiful and unique. Several stained glass originals make for excellent lighting even with the slightly low ceilings. Fascinating small details have been left the same way Clara Barton had it, including the varying floor levels which indicate the many renovations Clara Barton did to her home over the years. The home has what Clara Barton referred to as the warm belt, a series of connecting doors on the second floor bedroom area. This warm belt would provide heat to the adjoining rooms with a centralized fireplace in her bedroom. Original cotton muslin still exists in a storage closet area on the second floor as well as an original bathroom. Outside, a large southern Magnolia tree bigger than the house provides a lovely private view, this tree is debated over whether or not it is historically significant. It is referenced but not photographed, nonetheless a beautiful tree.

The days following my visit to Clara Barton’s National Historic Home were spent teleworking. Despite the more immediate threats of Covid being minimal, it is nice to have opportunities to work from home and minimize contact with others as much as can be done. I prepared for continuing site condition assessments with Cultural Resource Specialist Megan Bailey, this time on the north parkway Mount Vernon trail section of the GWMP. I collected Latitude/Longitude GPS coordinates by searching through archaeological reports on this section of the parkway. This is to aid in the site identification process when we go to the field later this week.

On July 5 we ventured back out into the field, driving along the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway, the earliest portion of the GWMP, extending to George Washington’s Mount Vernon. This segment of the GWMP was built in 1932 to commemorate the bicentennial of Washington’s birth. The earliest inhabitants of this area were Algonquin speaking tribal groups. They lived in villages along the shore, usually near large streams that entered the Potomac River. Today, many from all over the world are attracted to Mount Vernon as the birthplace of our first president. The GWMP serves as the most direct access to Mount Vernon via the MVT. Along the Mount Vernon Memorial highway are also many important cultural and natural sites like Belle Haven, Dyke Marsh, Jones Point, Arlington House and Slave Quarters, Roaches Run Waterfowl Sanctuary, Collingwood, Fort Hunt, and of course the titular Mount Vernon house and gardens, among others.

We hiked to several historic plaque sites to assess their conditions and need for conservation work. Using descriptive info like trees nearby, we carefully navigated the highway. Some areas were extremely overgrown since it is summer, making it near impossible to locate sites with precision.This required making several visits throughout the week. One trip focusing on the Northbound side, the other on the Southbound. NPS Cultural resource specialist Megan Bailey and I, trekked to Jones Point park, the Netherlands Carillon, the U.S. Marine Memorial, Arlington House, and Belle Haven Marina.

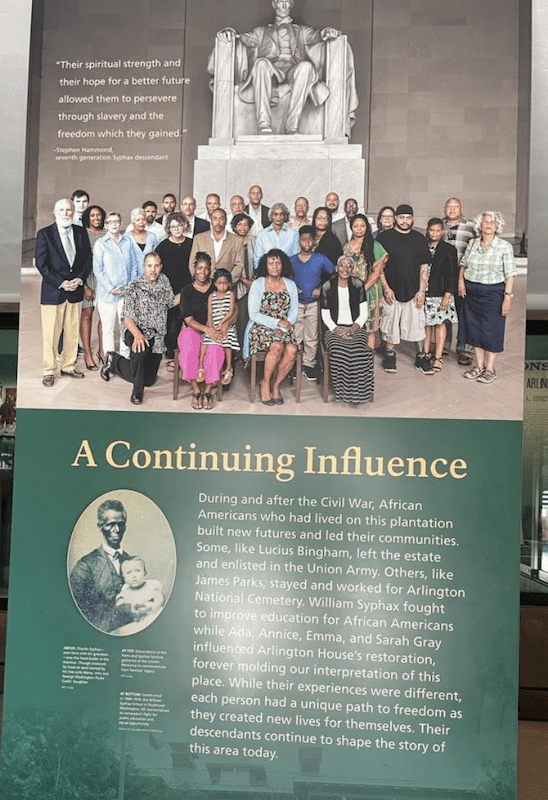

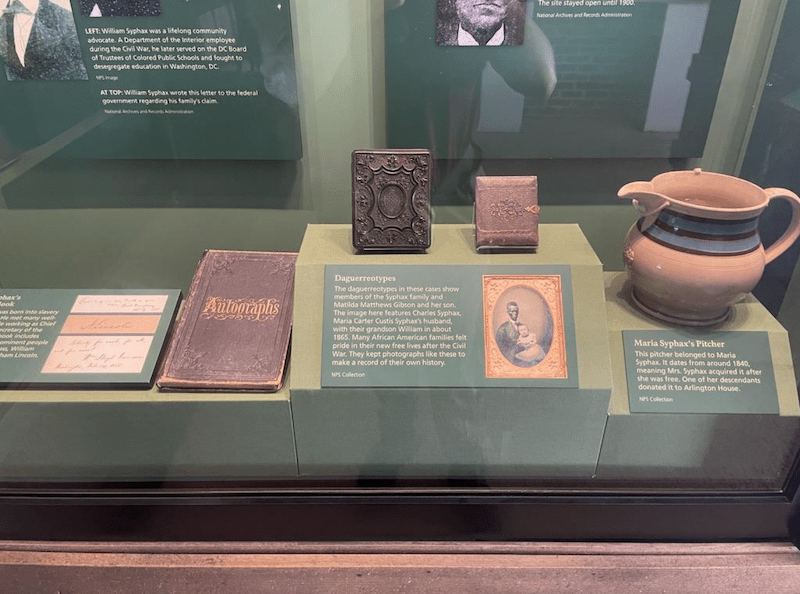

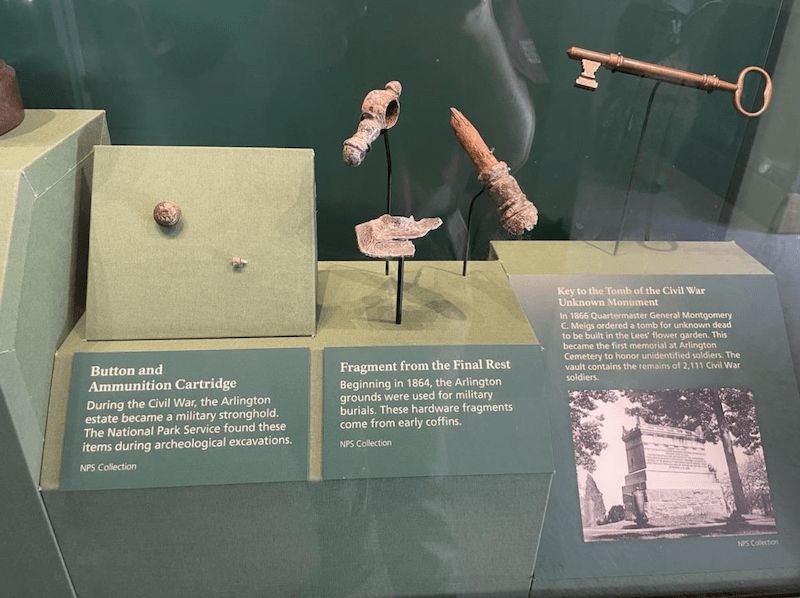

At Arlington House I spent a bit more time exploring and taking in the exhibits on the quarters for the enslaved people that lived at the home during the Custis-Lee period. The North and South quarters sit directly behind the main house, in nearly a historically accurate representation of what the structures would have looked like during this time. The interior of the slave quarters have been converted to museum exhibitions describing the lives of the families that called it home. An exhibition space in the far right room shows a replica of the living space of Selina Norris and Thornton Gray. They lived in this small space and raised their 2 boys and 6 girls here. The center room, the smoke lodge, has a powerful message by the descendants of the enslaved Thornton Gray and Syphax families. It invoked the visitors to take a moment and sit with the legacy of Arlington House in the history of slavery in the United States. For generations, the legacy of slavery has impacted millions of families who still deal with the repercussions to this day. The trauma experienced and the commitment to their families is clearly depicted. The last room on the right shows a further in depth timeline and several artifacts on display linked to the quarters. The southern slave quarters is the site of the archaeological collection I will be cataloguing later in my position with NPS Museum specialist Erin Coward and archaeologist Karen Orrence.

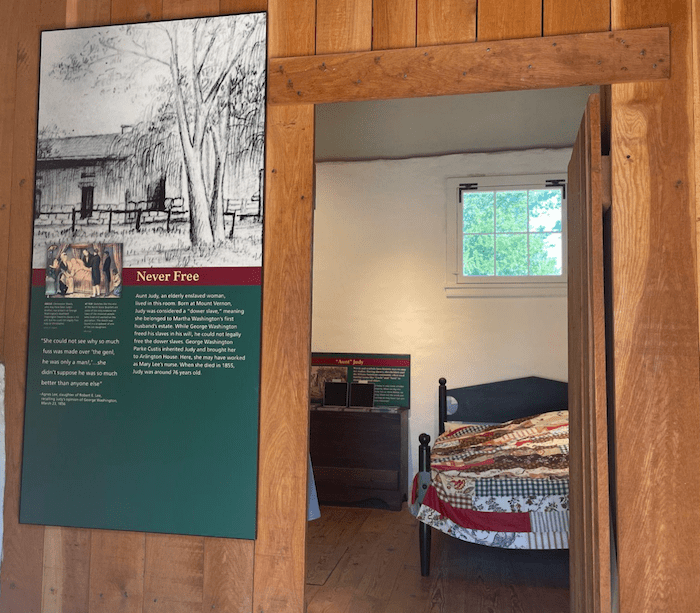

The North quarters was the home of George Clark, the cook, and Ephraim Derricks, the valet and gardener. Though married, neither of the men’s wives lived on the estate. The grim reality for many enslaved families, separated from their loved ones. The North quarters also previously had the summer kitchen, which would have made the space unbearably hot for the two men during Virginia’s humid summers. Aunt Judy was another enslaved woman who lived at Arlington House slave quarters. She was a “dower slave” who died in 1855, probably around the age of 76 years old. Little is known of the individuals who lived and worked at Arlington House, their existences only recorded in inventories and the few remaining sketches/photographs.

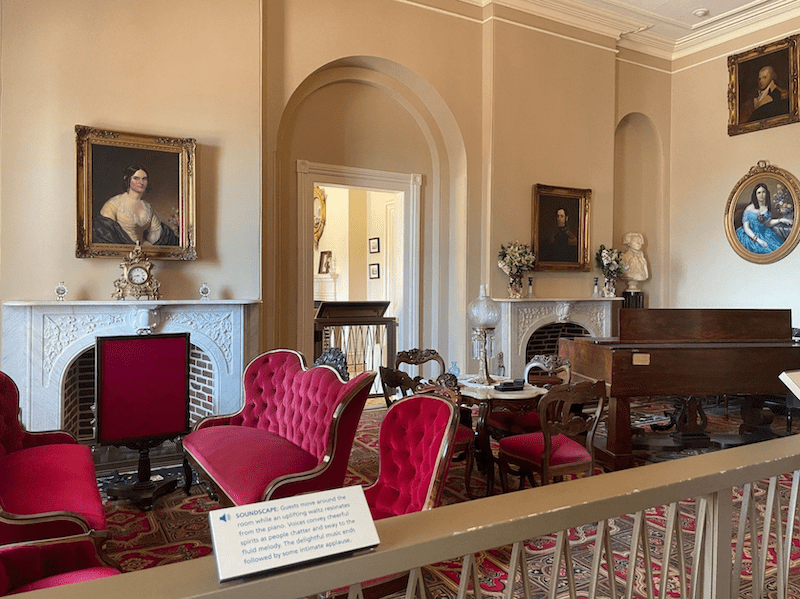

The inside of Arlington House has many recreations of the Custis-Lee residence. The interior of the Arlington House is even more extravagant with beautiful paintings of landscapes and portraits, expensive pianos and furniture, etc. The structure sits atop a hill with a powerful panoramic view of Washington DC and the national monument. The foreboding house hides the view of the enslaved quarters situated just behind the main structure. A design element that was carefully planned, no doubt. The juxtaposition is palpable when comparing the insides and outside designs of the structures. The main house with its huge looming lavishness, and the enslaved quarters hidden and sparse. I spent extra time at the quarters of the enslaved people at Arlington House because as part of my position I find it incredibly important to engage with the dark pasts that our history must reconcile with. I am honored to be part of a larger project to engage descendant communities and find a space of reconciliation, maybe even reparations, come the future. The artifacts uncovered from this site hold valuable insight into the lives of the enslaved people, it is possible to make sense of a community that has been strategically left out of cultural conversations and historical records. I hope that NPS will continue this type of work, not just for legal requirements, but out of an understanding that this is where real important connections can be made with people today. Especially in recent years of political and social tension, it is refreshing to see most people get on board with changing things.

These historic homes hold so much valuable information to directly connect professional archeologists, historians, and visitors to our shared American history. We need to be reminded of all parts of the historical records, including those which definitely demonstrate the lasting effects of race and gender based oppression in our country.