Inventory Adventures

Written by: Christina DadyEsposito

I was fortunate enough this summer to accompany the curatorial staff here at the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site (MAVA) on two little field trips. Both for inventory purposes. From what I gather, the National Park Service is exploring the idea of centralized locations or “hubs” for collections. MAVA stores their archeological collections at Fort Stanwix National Monument. Their museum collections are stored at the Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt. (NPS tidbit: the Vanderbilt Mansion and Eleanor Roosevelt site are administratively part of the FDR site and so the place is called ROVA for Roosevelt-Vanberbilt by NPS staff.)

As other ACE members have shared over the summer there are different kinds of inventory that museum staff conduct. Random inventory and controlled property inventories are the ones that I assisted with. Both present an opportunity for behind-the-scenes sneak peeks.

The Fort Stanwix trip occurred on my third day on the job. It is hard to argue against the consolidated storage plan when in such facilities as those at Fort Stanwix. I haven’t been in too many storage areas for museums and libraries but enough to know that space is always a premium and open shelving space for growth is rare. I have no archeological experiences so it was fascinating to see how those artifacts are stored and accounted for.

Since that trip I have spoken to MAVA’s superintendent Megan O’Malley and attended a talk by Jeff Bendremer, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer, to learn about how the tribes most closely affiliated with MAVA, particularly the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of the Mohican Nation, feel about archeological artifacts. Bendremer was able to dig into the complicated relationship tribes in general have with the field of archaeology (especially as the field is steeped in western colonizing thought and practice). Tribal partners have expressed interest in leaving archeological artifacts where they are in the ground rather than have them dug up, boxed, and stored on a shelf. From their perspective, leaving the artifacts in the earth is how they choose to preserve them.

I thought it worth sharing this long tangent from a single inventory experience because it highlights how the treatment and organization of cultural and natural resources can vary from culture to culture. What is valued, how it is valued, and how it is shared or disseminated with the public or those outside the cultural group greatly impact how those artifacts or information is organized. This is crucial context that can be easily lost from the effects of time, language, and/or space and I like to keep it in mind when handling any kind of artifact or paper.

The inventory trip at ROVA was much more of a good old fashioned treasure hunt. I got to see how rugs were conserved (and embarrassingly flat out asked if that was the proper way since it really just looked like they were rolled up), the stacks for ROVA archives and art works, drawers for historic wallpaper storage, and oogled over the space and supplies they have. The inventory process at this site once again demonstrated the need for strong records organization. Locating and identifying items is only a treasure hunt if you have a good map. Otherwise it is a “needle in a haystack” effort of frustration.

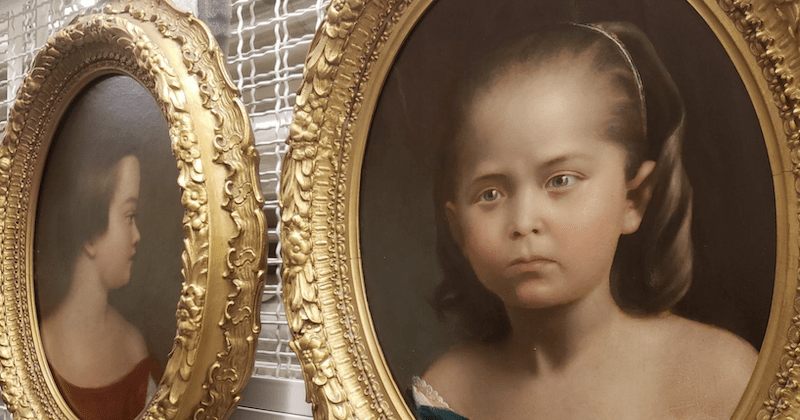

Find of the week: I got to meet the haunted twins of MAVA. A set of portraits that were acquired with a group of other artifacts and live to haunt the stacks of ROVA.

“Silences enter the process of historical production at four crucial moments: the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).” ~ Michel-Rolph Trouillot