The Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and Cato

Written by: Jada Yolich

For this final week, I want to introduce what has been my most significant find in doing research at Independence. Cross-referencing fugitive slave ads with 18th century tax records, I’ve found a link between the inkstand used to sign two of the three Charters of Freedom, the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, and the use of enslaved labor.

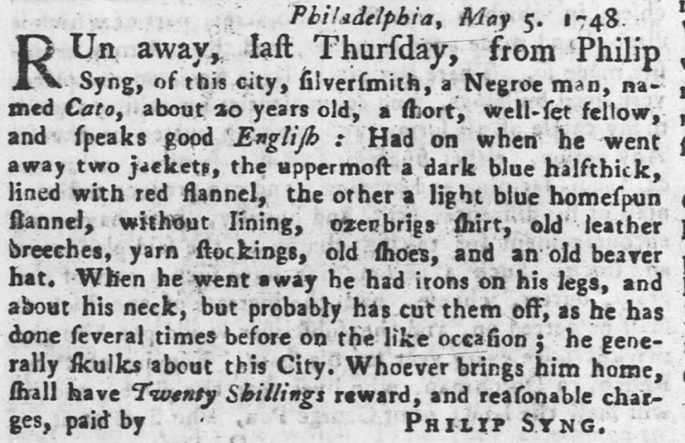

After transcribing fugitive slave advertisements between the years of 1730 and 1780, I came across one published by a Philip Syng in 1748 in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. The ad initially caught my attention because it described the runaway enslaved person as having had on chains around his neck and legs when he escaped. It was also published in the city of Philadelphia, a Northern urban center where enslaved Black people were known to often work alongside white sailors at the docks and slavery was thought to have taken on a milder form than what existed in the South, so this was something unusual. Cato, the enslaved person who ran away, was also noted as having been wearing leather breeches when he fled. This heavily implicates Cato as some kind of worker, or blacksmith.

But it actually gets even more interesting. Philip Syng was the renowned colonial silversmith who crafted the Syng Inkstand, the inkstand I previously mentioned. It was the tool used to sign American abstractions of freedom and independence into being but it was also an object likely created by enslaved African artisans. We actually have this artifact on exhibit at Independence, but nowhere is it mentioned in its interpretation that it was likely created, or at the very least partially created, by an enslaved person.

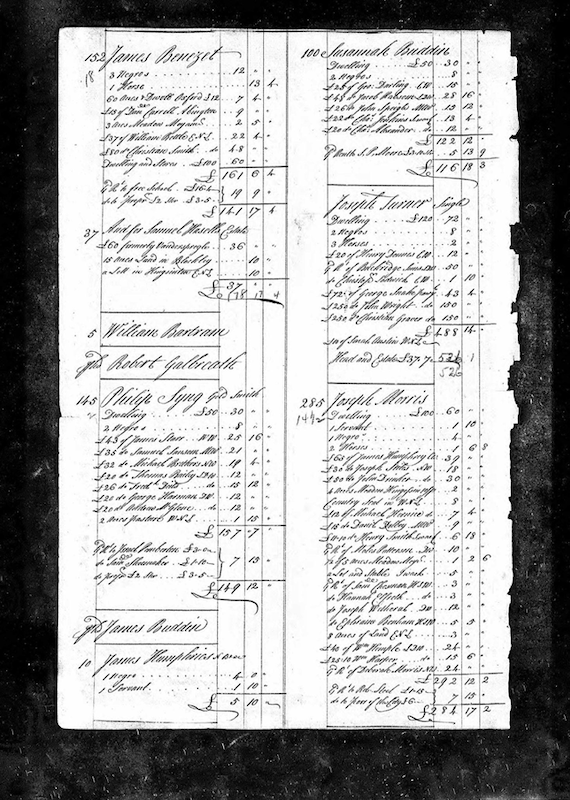

I believe Cato worked on the inkstand, and if not that very piece, something else branded as Syng’s. The inkstand was created in 1752, and the ad for Cato was published in 1748, only four years prior. Cato was also only twenty-years-old at the time of publication, so he still would have had many years ahead of physical labor at twenty-four, in 1748. I also found a 1769 tax record belonging to Philip Syng that showed him paying taxes on two enslaved people, roughly twenty years after the Cato ad was published. Although I was unable to confirm if one of those enslaved people was Cato, that might have very well been the case. And even though I have ideas about what happened to Cato, I cannot soundly conclude whether Cato was recaptured or found freedom.

This was a really big find for me because there are a lot of broader implications that accompany this historic reinterpretation of the Syng Inkstand. It highlights the dichotomy of liberation and enslavement that undermined early American political doctrines and systems. This was sort of the pinnacle of my research and I’m excited to share it with everyone!