San Juan Island National Historical Park (SAJH) was established on September 9, 1966 by the U.S. Congress in Public Law 89-565 for “… the purpose of interpreting and preserving the sites of the American and English camps on [San Juan] island, and of commemorating the historic events from 1853 to 1871 on the island in connection with the final settlement of the Oregon Territory dispute, including the so-called Pig War of 1859…” Additionally known for its spectacular views, natural landscapes, and wildlife, San Juan Island is an important site in the history of the United States, British Columbia/Canada, and international politics more broadly.

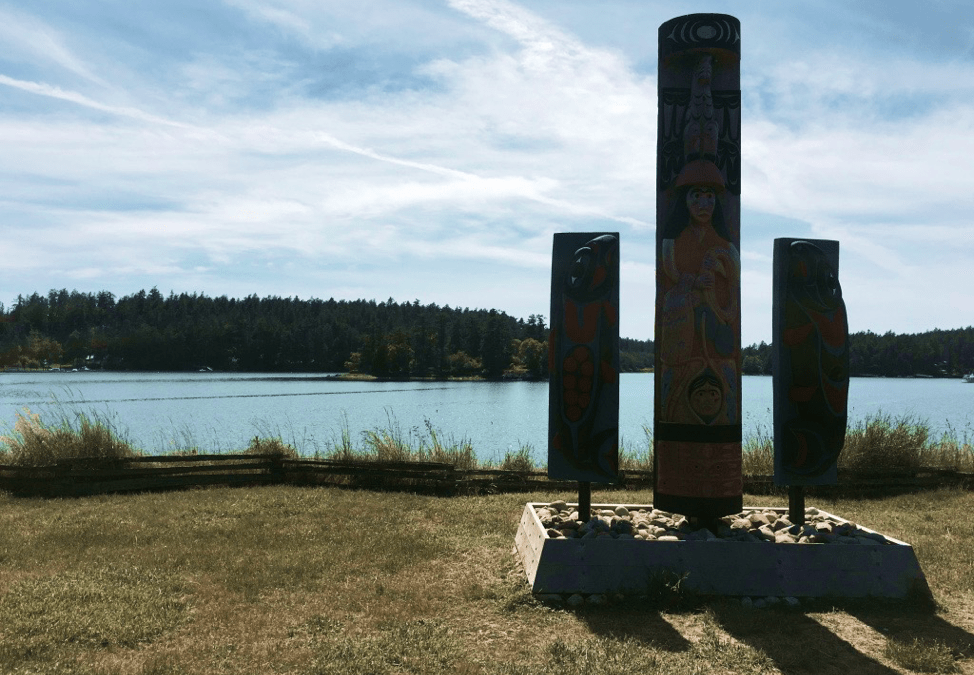

In recent years, the SAJH has grown to expand upon its founding mandate. With the installment and dedication of a Reefnet Captain Totem Pole and two Salmon Story Boards on August 25, 2016, representatives of the Lummi Nation and the Saanich First Nation returned to an ancestral village site known as Pe’pi’ow’elh, now located within the northernmost “English Camp” unit of the San Juan Island National Historical Park. And while I spend most of my time at the park’s southernmost “American Camp” unit, my first visit to Pe’pi’ow’elh sparked my own interest the importance of the park’s contemporary responsibilities to the region’s Native American communities. Collaborative relationships to safeguard the many cultural, natural, and often painful landscapes of the San Juan Islands, nevertheless, are not merely efforts to “diversify” a set of mid-20th century interpretative themes for various publics. Rather, as I have come to appreciate during my short time here, these events are part of an ongoing process of cultural revitalization, education, and healing from the past and current traumas of colonialism.

On June 22, 2017, I was honored to attend a “Coast Salish Cultural Day” event at Pe’pi’ow’elh (English Camp) at the beginning of my CRDIP internship. Taking a short canoe outing in the waters of Garrison Bay with representatives of the Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, the Samish Indian Nation, and other Coast Salish tribes and nations, the notion of collaborative stewardship took on a completely new meaning. Being present with Coast Salish Elders, families and youth; community members and visitors to the island; and my park colleagues at the close of the day’s celebration has been one of the highlights of my experience as a CRDIP intern thus far.

For additional information on the interpretive themes of the San Juan Island National Historical Park, visit the park’s website. Additionally, see Daniel E. Coslett and Manish Chalana’s 2016 essay “National Parks for New Audiences: Diversifying Interpretation for Enhanced Contemporary Relevance” in The Public Historian, Volume 38, Number 4, pages 101-108. Information on the aforementioned events can be found at indiancountrymedianetwork.com.