From Kamloops to Carlisle?

Written by: Eric Chiasson, Tribal Policy Analyst Intern, Tribal & Cultural Affairs, NPS-Region 1

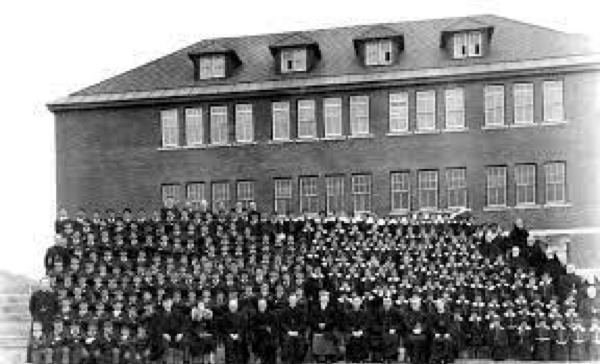

Our government’s formal recognition of Juneteenth as a federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States is an important step toward confronting in a meaningful way that institution’s enduring legacy. The move, hopefully, opens the space for sustained national dialogue about race relations, history, and the content of ‘social justice.’ But the United States is not the only nation-state on the continent grappling with issues related to national identity and a past reverberating into the present. In Canada, recognition of Juneteenth in the U.S. coincides with discovery of the remains of 215 children at the site of a former residential school for indigenous children in Kamloops, British Columbia. The school operated between 1890 and 1977.

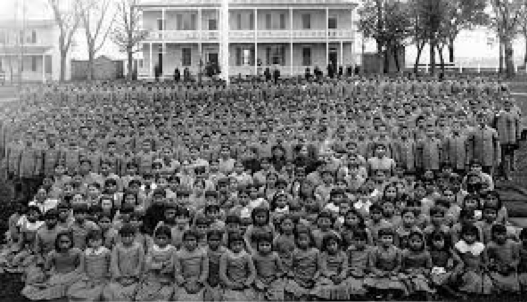

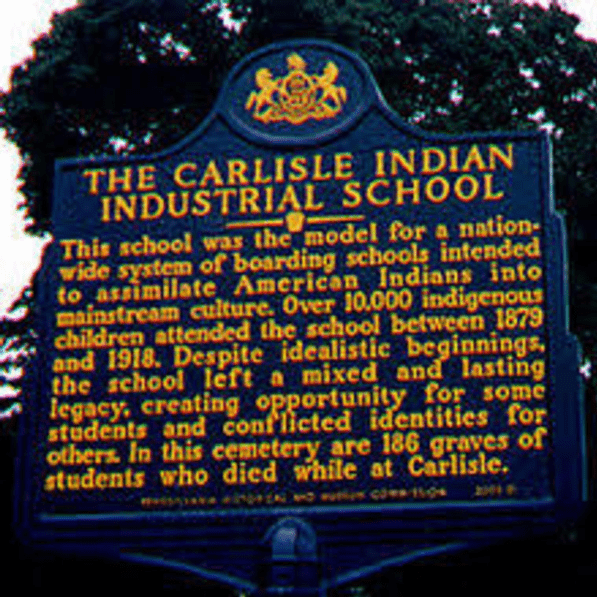

The discovery of the unmarked mass grave at Kamloops comes in the aftermath of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s 2015 multi-volume final report and the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. The idea of confronting honestly while honoring a traumatic past forms the nexus between events unfolding in British Columbia and a CRDIP internship focused on Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) compliance in the National Park Service. The reality, of course, is that the United States also administered a system of residential schools for indigenous children. In fact, the Carlisle Indian Boarding School Cemetery in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, is readily identifiable using Google Maps. It is on military reservation land; situated between an AAFES PX and the US Army Carlisle Barracks Visitor Center, just across the way from Jim Thorpe Road. You will find no national monuments memorializing the legacy of forced assimilation. Although, there is a municipal plaque referencing good intentions and mixed results.

NAGPRA is legislation about balancing the interests of Native American communities in their ancestral remains and objects of cultural patrimony—contained in federal institutional collections—with the interests of the museum and scientific communities. The challenge in maintaining such a balance is that the field of statutory interpretation is not fixed, and neither is public sentiment. Events in Kamloops appear to be accelerating efforts already underway at the Carlisle Barracks to disinter remains of indigenous children said to have succumbed to diseases. But a larger question remains: Carlisle is largely known for being the site of the Army War College, but—in the spirit of reconciliation—would it not also be an appropriate place for the American public to learn about the story of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School and the evolution of federal-tribal relations in our country?