DRAFTING FOR THE 20TH AND 21ST CENTURY LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT

Most people think of working for the National Parks Service as getting to spend lots of time outdoors, going on hikes and nature walks, doing landscape maintenance work, and generally getting one’s hands dirty. While we get to do a lot of that as interns at the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, we are being introduced to another important side of the NPS’ work in our nation’s parks: the profession of landscape architecture. The Olmsted Center was named after Frederick Law Olmsted, after all, the father of landscape architecture in America and the designer of many of the most famous parks in the country, including Central Park in New York City, Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, and the Emerald Necklace in Boston, among many others.

As with architects who design buildings, knowing how to draft accurate site plans is an essential skill for any landscape architect. Creating up-to-date site plans will also be a central part of the Cultural Landscape Inventories (CLIs) that Jill, Catrina, and I are currently preparing for the Baker-Biddle Homestead, Long Island in the Boston Harbor Islands, and the Pamet Cranberry Bog, respectively.

My degrees are in history and architectural conservation, so I personally have had little exposure to architectural drafting software, outside of self-teaching myself how to use Revit. Thankfully, we had a savior in the Olmsted Center’s Tim Layton, who graciously came up from Richmond, VA to give us an intensive four-day workshop on everything we would need to know to get started on our own site plans. This included a crash course on a number of essential software programs: AutoCAD, ArcGIS, Adobe Illustrator, Adobe InDesign, and even a quick primer on LIDAR scanning. It was a lot to process in a few short days, but we couldn’t have asked for a better teacher than Tim!

Last week, we took a break from the office to pay a visit to Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site – the site of Olmsted’s design firm and the world’s first professional office for the practice of landscape architecture – to see how landscape architecture was done in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. After a week of fumbling my way around AutoCAD and ArcGIS (lots of exploratory mouse-clicking and calling Tim for help), our visit was both a literal and figurative breath of fresh air.

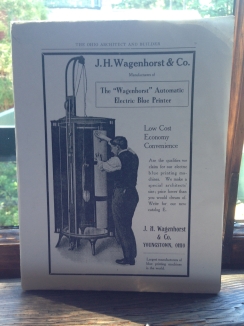

It shouldn’t have come as a surprise, but what struck me most during our visit was the contrast between drafting techniques in Olmsted’s time and today. In Olmsted’s day, everything was measured and drawn by hand, including the numerous copies which had to be made (usually by apprentices – our turn-of-the-century equivalents – who had to meticulously trace over the original drawings). We even saw an early 20th century blueprinting machine, which looked like something out of a sci-fi movie or Victorian magic show. Walking through Olmsted’s drafting workshops – strewn with the various tools for hand-drawing, measuring, copying, and printing – I found myself longing to learn the old methods, to put pencil to paper and use my own hands to create something.

My intern colleagues rightly pointed out that making changes to one’s drawings or printing a copy is infinitely easier to do using today’s digital methods, and I understand the enormous advantages that digital drafting technology presents for the profession. Part of my skepticism comes from the fact that, one, I love drawing, painting, and crafting with anything I can get my hands on, and, two, I’m a bit of a romantic at heart. As I become more comfortable using these digital drafting programs and the barrier of knowing simply how to do something begins to fall away, I’ve found myself enjoying the creative process more and more. I’m looking forward to improving my skills over the next few weeks and finding out what I can do with them….but I still miss my old pen and paper.

Until next time,

Clare

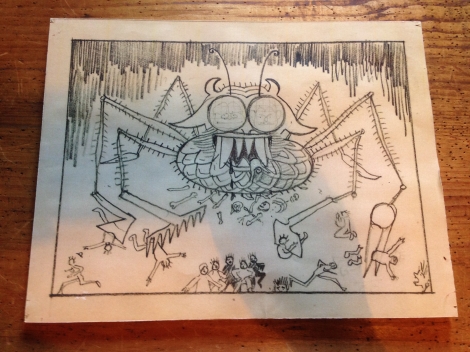

I don’t know what prompted one of Olmsted’s colleagues to draw this terrifying cartoon, but I hope drafting never makes me feel like I’m being eaten by a giant spider.