Written by ACE Member: Maggie Weaver

We all remember those first few days at home when quarantine started. We slept in, ate breakfast for lunch, put on a nice shirt for Zoom meetings while secretly still in our pajama bottoms, browsed the internet for new hobbies, and scavenged the store for seemingly nonexistent toilet paper packs. As days turned into weeks, and weeks to months—as our dogs’ hope that we took the rest of our lives off to entertain them solidified alongside our cats’ despair over their daily nap interruptions—we even began to see nature thrive more in our absence. However, the stories about more swans and dolphins enjoying the Venice canal waters with the new lack of boat traffic were soon debunked. Disposable face masks became hazardous environmental threats, their litter increasing plastic pollution and further disrupting marine habitats. Poachers and loggers became more active as law enforcement stayed home. Disillusionment about nature ‘healing’ even loomed close to our own homes. While it seemed as if more squirrels were hopping our backyard fences or more birdsong was audible amidst the absence of highway congestion, at the same time more people started to frequent nature, creating a situation far from human absence. We too grew antsy, and felt an increasing urgency to keep moving, even if the world around us seemed at a chokehold. So we turned to the place that seemed the safest and most open—the most place feasible to social distance and stay COVID-safe. We knocked on nature’s door.

The longer stay-at-home measures endured, the more guests nature had to accommodate in her “alfresco abode”. On top of a wide variety of media reports, a UVM study recently found that more Americans have been visiting nature during the pandemic. I have seen this firsthand: a lot of my friends who were previously infrequent hikers, campers, or even outdoor goers in general, have changed their habits after too much time at home. There are several factors that should be noted when internalizing this observation. Firstly, more nature-goers is not an all-around unpropitious occurrence. While an upsurge of nature-goers does further strain outdoor spaces and calls for more emphasis on Leave No Trace principles, the upsurge also increases opportunity for a more influential nexus between humans and the outdoors. This concordance is now crucial to embrace in order to move towards a more auspicious future for our climate. Finally, with these two factors in mind, it is important to understand and appreciate the multifaceted role that trails— our gateway and sustained point of access to nature’s territory—play in all of the above details. If we want to continue to frequent nature’s space, we must recognize and advocate for trails not just as recreational systems, but also as critical tools for conservation.

“Before I came to ACE, I didn’t really think of trail work as conservation. I saw it as more of a recreational endeavor, as a means to help promote physical activity,” Southwest corpsmember Claire Schu explains about her previous perception of trail maintenance and construction. This perception was also true for my pre-ACE experience, and is true for many people in general — when we think of trail work, conservation is not often the first word that comes to mind. This is why ACE Southwest Conservation Trainer and Coordinator Jimmy Gregson likes to explain trail work as a more seemingly ‘indirect’ act of conservation: “Initially, I viewed conservation as a very academic pursuit. Researching and studying to better understand the natural world in order to protect and restore endangered ecosystems. Joining ACE gave me an appreciation of the on-the-ground, realistic implementation of conservation practices. I better understood that conservation is not all directly studying endangered species or environments. Conservation can be a little more indirect, like trail work”. Indeed, it is quite hard to imagine the act of tearing up earth and carving human impact through wild spaces— in order to create what we assume is primarily for our own enjoyment— as an obvious conservation practice. Yet, the reality is that trail work is a firm and direct conservation practice for two primary reasons. First, trail work mitigates human impact on the environment; second, it inspires further conservation.

Trail work’s main conservation value is, as Jimmy puts it, “to reduce the wider impact of anthropogenic activity on our public lands and sensitive ecosystems”. Trails or no trails, human wanderlust will prevail, and people will still try to engage with the outdoors in any way they can. Thus, if there are no established trails, or if trails are not maintained, people would be able to explore nature wherever they wanted to, creating multiple scattered adverse impacts on sensitive environmental areas. Fortunately, thanks to trails, human impact is concentrated in specific designated areas (which Jimmy calls “corridors of impact”), protecting sensitive ecological areas and allowing nature’s already altered spaces to be more easily and sustainably maintained.

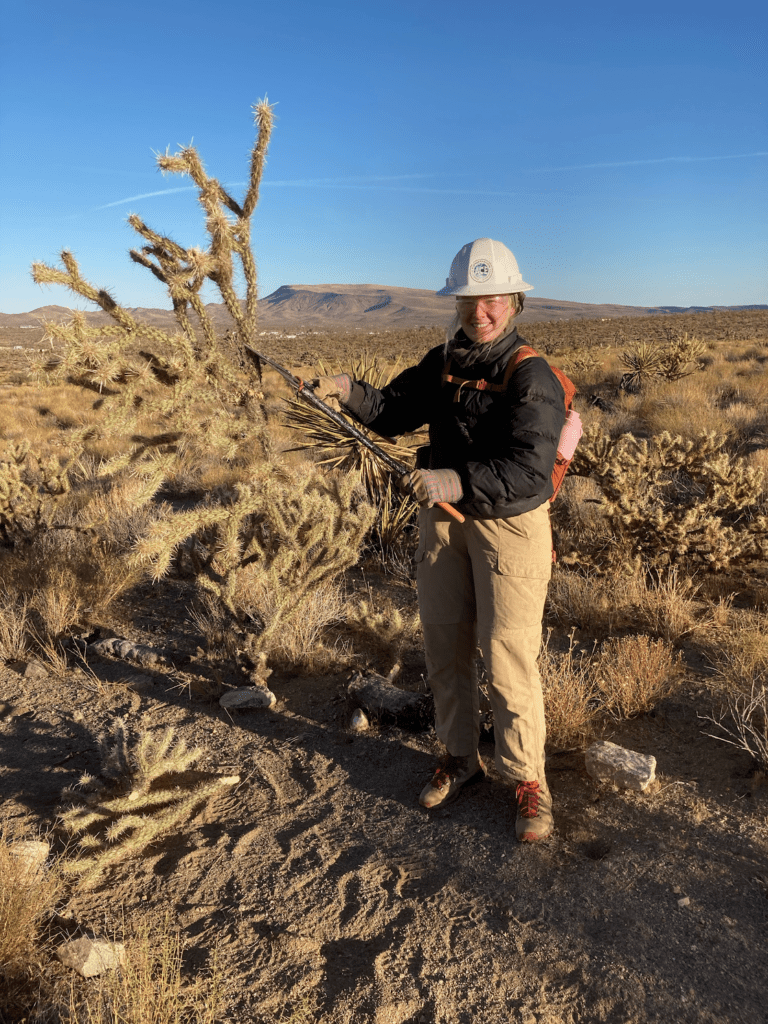

In my experience with ACE Southwest so far, I have helped bolster sustainable trail layouts for eclectic uses (primarily bikers and hikers) and weather conditions (mostly rainfall and flooding). My first trail work experience was in Dolan Springs, AZ, where my crew layed out several trail reroutes, altered tread, and either fixed or installed drains to help with erosion control in the event of heavy rains. ACE also does several other kinds of trail conservation work to maintain public trails across the country. The work can involve anything from simple drain improvements, such as on my Dolan Springs hitch; to rockwork for erosion prevention, staircases, and retaining walls; to backcountry Wilderness Area trail maintenance, where only crosscut saws are allowed (thanks to the Wilderness Act of 1964, which designated certain areas under the highest levels of federal land protection and established regulations such as no motorized engines in order to keep these areas as wild and pristine as possible). Southwest Project Manager Victoria Niedzielski expresses that backcountry trail work is one of her favorite types of hitches, voicing that “Wilderness trail maintenance is really important when it comes to conservation.Wilderness is where Leave No Trace principles originated. Take only photos and leave only footprints. It’s really special to work in Wilderness areas; there’s a kind of magic there”.

Trails not only foster sustainable interactions with, but also intimate connections to, the outdoors. In this way, a second conservation value to trails is that they are powerful galvanizers for environmental stewardship and advocacy. Victoria echoes this, commenting that “making wilderness areas more accessible to people will hopefully inspire them to want to preserve. Also by maintaining trails, hopefully more people will visit the areas, giving the agencies that manage them reason to request more funding—so that these agencies can continue to protect and preserve these areas. We need people to care about the outdoor environment in order to help protect the entire world”.

Photos by: Lynae Bresser, Chris Fletcher, Maggie Weaver (ACE Southwest corpsmembers)