By Michelle Dempsey

For the past couple of weeks, I have been digging into secondary and primary materials related to voting rights and legislation in New York, the lives of northern and southern women in the antebellum period, New York’s place in the early women’s rights movement. I have also done some thorough digging online in the attempt to locate archives related to the women of Lindenwald, especially Angelica Singleton Van Buren, Martin Van Buren’s daughter-in-law, and Christina Cantine, his beloved niece.

The voting rights material has been super helpful in providing the basis of our voting history overview for fifth graders. Because the Hudson River Valley was home to Dutch-descended families who had built up quite a lot of land and wealth by the mid nineteenth century, Van Buren found himself both legally and politically in the midst of land disputes related to vast tracts of land belonging to families such as the Livingstons and Van Rensselaers and their tenants. Several small uprisings occurred in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries regarding the land charters, and by 1821, various people were calling for a convention to reform the 1777 New York State Constitution, which contained property and freehold requirements for the election of various government and public offices. Some major concerns regarding voting rights in this convention were in relation to property requirements, public/military service, and race. While the 1777 Constitution did not specify the word “white,” the 1821 revision, while lessening the property requirement for white men, required African American freeholders to possess 250 dollars in order to vote, which excluded the vast majority of free blacks in the state.

Figure 3: Title page of report on 1821 New York State Constitutional Convention, courtesy of New York State Library

An interesting figure I encountered in this research was a runaway slave named James F. Brown who fled from Maryland to the Hudson River Valley in the 1820s. He ended up on the Verplanck estate, Mount Gulian, in Fishkill, New York. After starting out as a waiter for the Verplancks, after only ten years Brown had become the estate’s master gardener and head man, earning that privileged and rare status as a middle-class African American man. As such, Brown became quite involved in helping his neighbors maintain the property requirements for voting in the state. He also became an active Whig party supporter, later switching to the Liberty Party which advocated specifically for the abolition of slavery. Much is known about Brown from the diaries he himself kept for much of the rest of his life after reaching the Hudson River Valley. Because diary-keeping meant middle-class respectability in the antebellum period, demonstrating thoughtfulness in business, public, and personal affairs, Brown’s diary, as well as his level of local and regional horticultural success, revealed a man who strove for the uplift of the free black community.

Figure 4: The book Freedom’s Gardener: James F. Brown, Horticulture, and the Hudson Valley in Antebellum America (2012) by Myra Beth Young Armstead traces Brown’s life and journey from slavery to master gardener

My research into the world of Lindenwald’s women, on the other hand, has thus far been focused on Angelica Singleton Van Buren and Christina Cantine, as I had mentioned before. This focus largely stems from the significance of these two women in Van Buren’s life, as well as the interesting contrast they provide as historical characters. Angelica was born and raised in Sumter County, South Carolina, the daughter of a wealthy planter family. After finishing her education at the elite Madame Grelaud’s French School in Philadelphia, she was shortly thereafter introduced to Martin Van Buren, then president, and his eldest son Abraham, who was then serving as his secretary. This meeting, engineered largely by Angelica’s cousin Dolly Madison, would end in Angelica and Abraham’s marriage, and therefore, Angelica’s place as Van Buren’s de-facto first lady (his wife Hannah having died many years before). Angelica ran the White House, then Lindenwald for a time, but she and Abraham retired to New York City, where Angelica became involved in charity work. I have found a hint that she became interested in women’s rights (at least in relation to property and divorce) after her sister’s experiences with an abusive second husband and loss of property to that man.

While I have yet to find evidence backing that claim about her interest in women’s rights, we are yet hoping to find how Angelica felt adjusting to life in the reform-minded North after growing up in the more patriarchal and slavery-entrenched South.

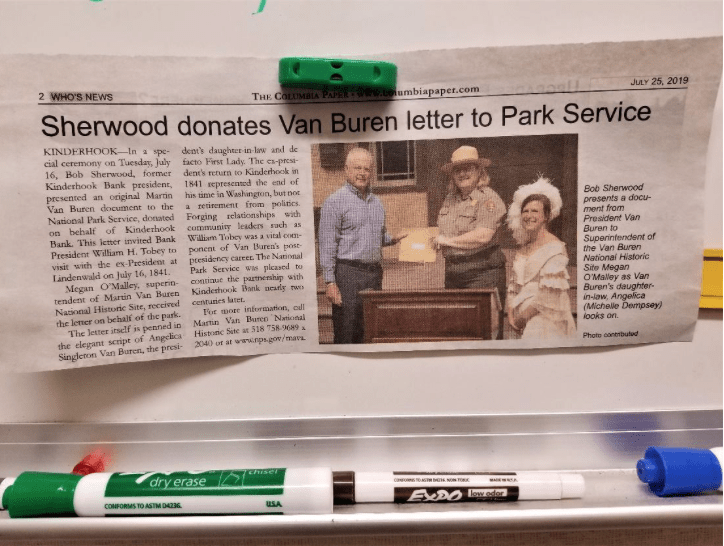

Figure 7: I got the opportunity to dress as Angelica for a document donation ceremony the other week!

Christina Cantine was Van Buren’s niece, the daughter of his wife’s sister (also named Christina). Christina grew up in Ithaca, New York, and, inspired by the evangelical revivalism that swept through the Burned-Over District of New York in the antebellum period, Christina maintained a religious zeal throughout her life. Van Buren had called her “a lady of remarkable intelligence and strength of character, and deeply imbued with religious feeling,” and remarked in his autobiography her passionate antagonism to Indian removal in the 1830s. He recollected her saying to him one night, referencing his support of and political closeness with Andrew Jackson, “Uncle! I must say to you that it is my earnest wish that you may lose the election, as I believe that such a result ought to follow such acts!” What we are hoping to discover over the next couple of months is whether this passion extended beyond indigenous rights to rights for other groups of people. We don’t want to assume that this feeling extended to other reform, especially concerning women, but we are thinking that Christina might, out of the women we know in Van Buren’s life, be the one to perhaps demonstrate some feeling about the condition of women.