Collaborative Present and Future

Written by: Diego Borgsdorf

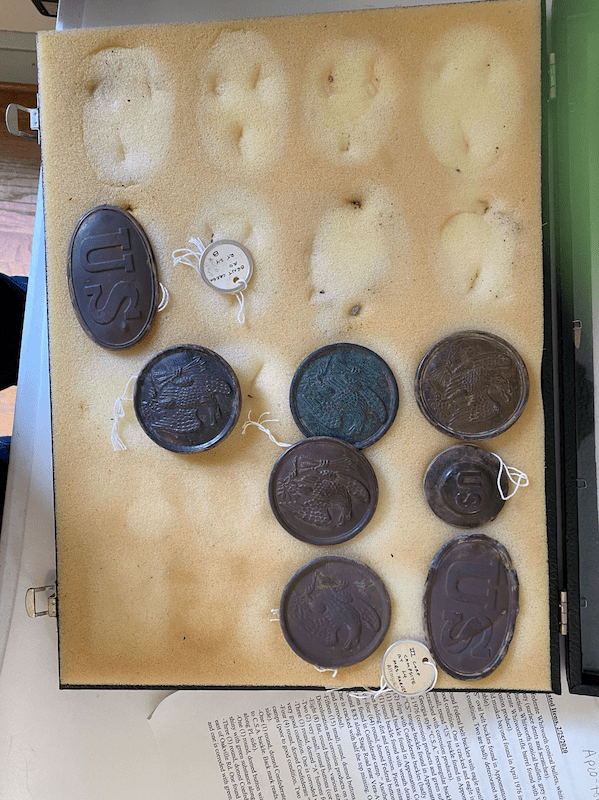

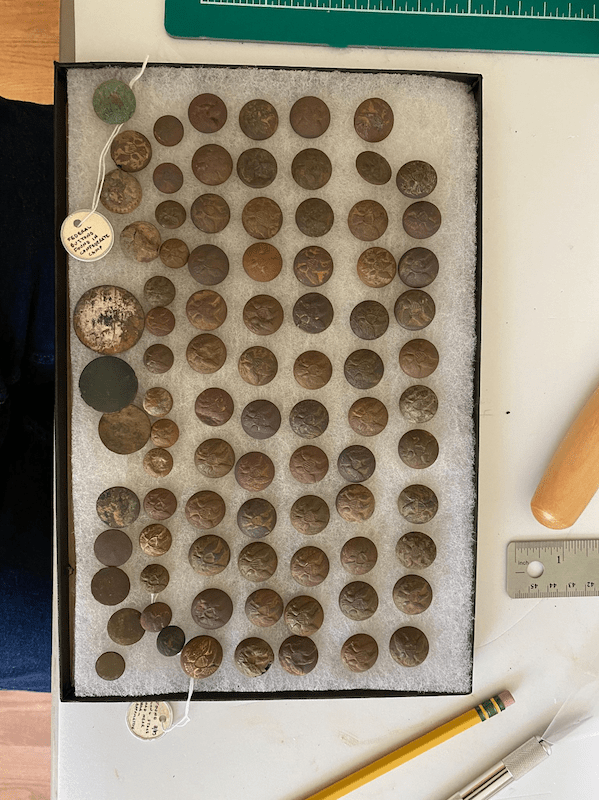

Over the past several weeks, I have embarked on the main project of my position this summer: cataloguing the Calkins Collections here at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park. At first, the challenge seemed daunting, and almost insurmountable. Stored across several shelves in curatorial storage were large shadow boxes filled with metal artifacts. The sheer number of artifacts—let alone my task of identifying, cataloguing, photographing, and re-housing them—was certainly a lot to take in. However, as I have begun this process, I have learned valuable lessons—not only about the intricacies of Civil War buttons, belt plates, or artillery fuses—but also, about the deep webs of collaboration responsible for historic preservation.

The Calkins Collections are the result of years of work by a retired historian from the Park. Through dozens of different off-duty discoveries made by the historian, hundreds of relics from the Appomattox Campaign in the local area were found. Upon administrative changes, the items were donated to the museum collections here.

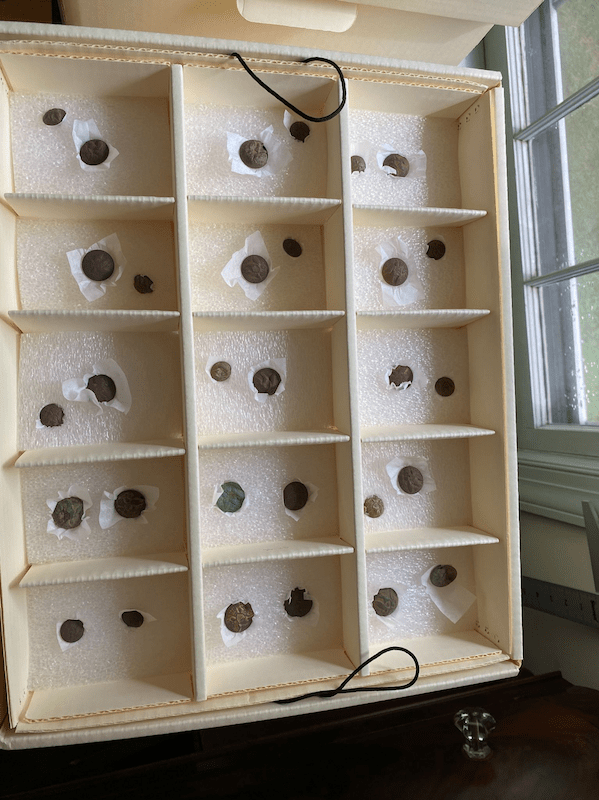

My role is helping out the CRM team here making sure that these precious, historically important items withstand the tests of time, light, and other agents of deterioration. Every day, I work to identify different objects from the shadow boxes, input important data about them into our museum management software, and then build museum-grade housing for them on, say, specialized types of foam that do not outgas chemicals over time.

Cataloguing these items has meant coming across incredibly fascinating relics from the time of the Civil War and the Appomattox Campaign. My favorite moments are when I get the opportunity to decipher and sleuth my way to identifying an unknown object. I remember one afternoon, I had come across a rifle lock plate, and I was stuck. The lock plate was pretty significantly corroded, so the markings that indicate the model and manufacture year of the rifle were heavily faded. I had scoured through my identification books, trying to make out what I could without seeing these markings, but I was having no luck. It was on what must have been my twentieth attempt at examining the lockplate with my closest eye under a magnifying glass that I saw it: a faint, small engraving of a federal eagle. A few centimeters away were marks that before, I could not have made out. The lock plate had the word “Springfield” on it! It was a lock plate from a Springfield rifle! As I went on to identify its specific model and year, I was thrilled. I finally could make sense of the metal fragment lying before me.

These types of moments are ones usually made behind the closed doors of museum facilities. In my case, nerding out over finding markings on a lock plate was a moment I relished alone. However, one of the most thrilling parts of this position has been thinking about how this work is not done in isolation. For starters, a strong relationship brought to the Park the Calkins Collections. When I input data about these objects into our software, it will benefit not only current and future museum teams at APCO, but also researchers interested in learning more about these invaluable objects. Re-housing these items ensures their longevity—meaning that my work is allowing me to connect generations yet to be born with a unique moment at the dusk of the Civil War.

The work I do is the result of a web of collaborations, and it is a part of future collaborations. It is an immense privilege to be a part of this work, and I couldn’t imagine anything more rewarding. As the Collections dwindle down into more manageable, acid-free boxes, I cannot help but feel elated for the opportunity to take on this challenge.