Halemauʻu: What’s a ‘subalpine shrubland?’

Written by: Jacob Hakim

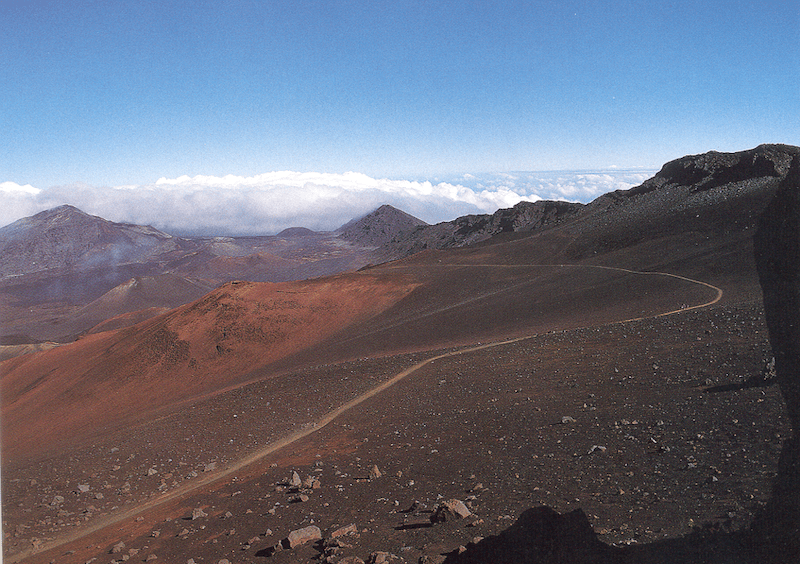

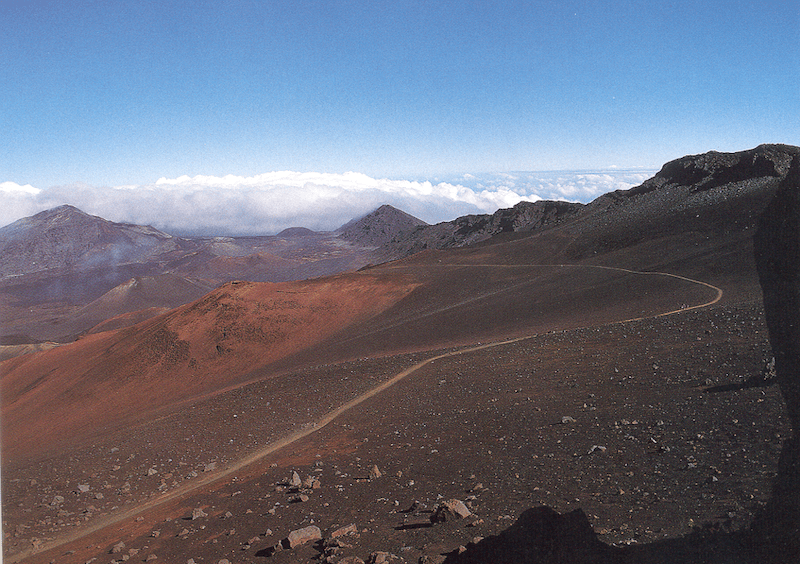

When working at the desk or roving around the Visitor Center, the most common question I hear is “What are some good hikes in the park?” Hiking is the most popular activity in the park (after sunrise/sunset viewing) and with good reason: walking through the fantastic landscapes in the park can feel like exploring the surface of an alien planet, especially down in the crater. There are more than 30 miles of hiking trails in the crater, but only two ways in. The first and most popular way down is the Keonehʻeheʻe (pronounced KAY-OH-NAY-HEY-EY-HEY-EY – try it!) or ‘Sliding Sands’ trailhead, which starts at the Haleakalā Visitor Center parking lot near the summit. This aptly named trail features sweeping views of the crater, including its hills of colorful cinder, lava flows and precipitous ridges. This area is known as an ‘alpine desert,’ a climate classification characterized by high altitudes, temperature swings and very low precipitations; alpine deserts are also found in places such as Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania and the high mountains of Japan.

The other entrance to the crater is found down the road at around 8,000 ft elevation, nestled among green shrubs and trees – a totally different environment. This is the Halemauʻu trailhead (pronounced HAH-LAY-MAO-OOH). The name Halemauʻu literally means ‘grass house,’ and it’s not hard to see where the name comes from. Especially in contrast with the summit and crater areas, this lower elevation area of the park is densely populated with native Hawaiian plants that evolved for millions of years before humans ever set foot in the islands. This is a popular trail for shorter hikes, and it’s a great opportunity to get a look at the native landscape of the mountain. Halemauʻu is classified as subalpine for its location at high elevations just below the tree-line, where the landscape quickly transitions to the wide, barren expanses of cinder and rocky desert near the summit. In this subalpine region, which the Halemauʻu trail traverses, hikers can look out for native plants such as māmane (sophora chrysophylla) a favorite of the native forest birds; pūkiawe (leptecophylla tameiameiae), a pokey plant whose berries are favored by nēnē, our state bird; ʻōhelo (vaccinium reticulatum), which is closely related to blueberries; and hinahina (geranium tridens), the lovely and dainty silver Hawaiian geranium. These plants are classified as ‘shrubs’ because of their height and their multiple above-ground stems.

Halemauʻu is also home to many of Haleakalā’s native insects and animals. Passersby who stop to admire the quiet of the mountain will soon notice the buzzing of busy bees, and upon closer inspection, a whole world of activity appears around the flowering shrubs. Alongside the big black-and-yellow honeybees, which are non-native, little yellow-faced bees of the genus hylaeus zoom from plant to plant, drinking nectar and spreading pollen. These bees, which are found only in places that are populated by native plants, are solitary and live without a hive. They also don’t sting. Of the 63 Hawaiian yellow-faced bee species discovered, 7 are classified as endangered. Other insects include the Haleakalā flightless moth (thyrocopa apatela), an endemic moth found only on the slopes of the volcano, and the native potter wasps of the genus odynerus. If you’re fascinated by the miniature world of insects, Halemauʻu is teeming with life and there’s no end to the wonders and surprises found on every flower and under every rock.

As for me, I’m lucky enough to walk this trail a few times a week as part of my duties as an intern in the park. Equipped with a small pack, a radio and a canteen, I head out from the trailhead and walk the mile or so to the first major natural landmark, the often-called ‘Rainbow Bridge,’ a natural land ridge that occurs just before the trail quickly changes grade and turns into the famous Halemauʻu switchbacks. During these roves I get to see not only the wildlife that lives on the trail, but the adventurers and wanderers who are heading out to see the expanse of the crater, or heading up from a backpacking and camping trip to the crater floor. In these interactions I get to be an interpreter, a guide between worlds, connecting people with mysteries of the Hawaiian wild that might otherwise stay uncovered. That’s the best part of the job.

Learn more about American Conservation Experience.