Hidden History of Washington Square

Written by: Morgan Clutter

This summer at my internship at Independence National Historical Park, I am helping to preserve a cultural landscape, Washington Square, but why does is this landscape need preservation? At a quick glance, it seems like any other urban park. Here I will give a brief overview of Washington Square and its past.

Figure 1: Children play in the center fountain of Washington Square in Philadelphia. (2022, INDE)

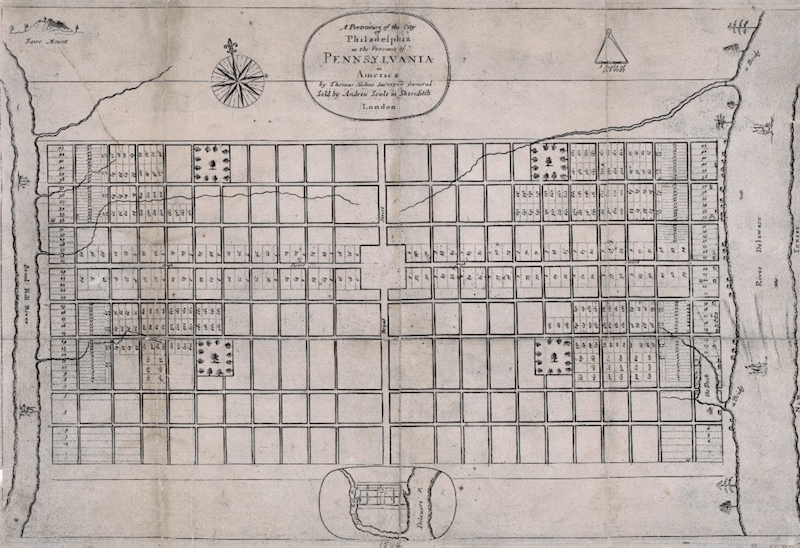

William Penn envisioned Philadelphia to be a “greene county town” with wide streets and public parks in reaction to plague and fire that Penn witnessed in London. So, Philadelphia was laid out in a grid with one center public square and one public square in each quadrant of the city. Each square was named for its location: Center Square, Southeast Square, etc. Washington Square (formerly Southeast Square) is one of the five original squares. It appears in the oldest recorded plan of the City of Philadelphia (Figure 2). In the early to mid-1700s, development of Philadelphia was primarily adjacent to the Delaware River and her ports. In this time, even the eastern most squares were still considered to be in the countryside or the rural part of the city. So, when William Penn issued a formal patent in 1706 for Southeast Square to be used as a burial ground to be used by all people, it made sense as it was on the fringes of the city. This is when Southeast Square became known as the “Potter’s Field” or the Strangers’ Burial Ground. From 1706 to 1794, Washington Square was used as a place to inter strangers, people unaffiliated with a religion, the poor, free and enslaved people of color, prisoners, suicide victims, and more.

Figure 2: 1683 plan of Philadelphia titled ” A Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia in the Providence of Pennsylvania in America by Thomas Holme, Surveyor General. Sold by Andrew Sowle in Shoreditch, London” (The Map Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia)

Additionally, during periods of expansive death in Philadelphia, Washington Square was used to inter those victims. During 1763, Christian Native Americans rounded up by British soldiers were being housed in army barracks in Philadelphia (supposedly for their protection), but an outbreak of small-pox swept the barracks. 63 Native Americans were buried together in one corner of Washington Square. In the winter of 1777-1778, under British occupation, more than 2,000 American prisoners of war & British soldiers died of cold, hunger, and disease over a particularly hard winter. The soldiers were buried together in pits the length of Washington Square. The last major event was in 1793 when 1,334 residents of Philadelphia, who died during a yellow fever outbreak, were buried together in Washington Square. After the yellow fever mass burial, Washington Square was officially closed for all public burials. A minimum of 3,397 people were buried in Washington Square. But individual internments or exact numbers of buried Revolutionary War soldiers were not documented, so the number is anticipated to be closer to 5 or 6,000.

Beyond burials, Washington Square has an extensive history. During the 18th Century, free and enslaved members of the black community used Washington Square as a gathering space and festival ground. One modern secondary source claims that Washington Square was also known as Congo Square during this time period, but surviving written primary sources do not verify that claim. However in 1765, began the decades long tradition of the black community patrolling the square at night to protect the dead from grave robbers and theft. Dr. William Shippen was notorious for hiring people to steal bodies from Washington Square, so he could preform anatomical studies. While horrifying, this period lead to the earliest surviving records of a well-documented member of the black community in Philadelphia, James Oronoko Dexter. A group of six members of the black community petitioned the City of Philadelphia in 1782 to construct a fence around Washington Square to make it easier to protect. The petitioners listed were James Oronoko Dexter, John Black, Samuel Saville, Cuff Douglas, Aram Prymus, and William Gray. Their petition was ultimately denied; similarly, to a 1790 petition by the Free African Society that asked the city to make Washington Square an official black cemetery.

At the time when burials in Washington Square were closed in 1794, the development of Philadelphia had reached the square. Instead of being a rural plot of land in the countryside, Washington Square was now surrounded by dense buildings on all four-sides. This led to the movement of creating a public walk or promenade for people to escape the city. In 1794 is the first documentation that the city is improving the square, when they planted a row of Lombardy Poplars on all sides of the square. Originally Washington Square was not flat like today. It had a deep gully, streams, and a duckpond at the south edge, but these features did not support a public, formal walk that the residents desired. In 1805, the City of Philadelphia decided to orderly level Washington Square by building brick culverts over the streams and filling low spots with debris. Which was followed very quickly to the first official design of Washington Square in 1816 by George Bridport. His design featured a circular design with diagonal paths to each corner and a central evergreen planting.

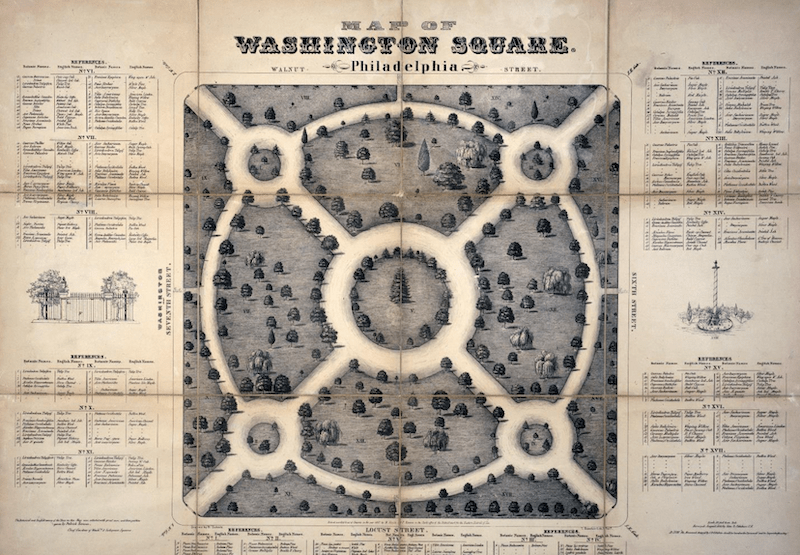

Figure 3: 1843 lithograph of an August 1842 survey of Washington Square by John B. Colahan entered according to an act of Congress in the year 1843 by M. Schmitz, P. Kereven in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the Eastern District of PA. By this time, the iron fence shown at left was in place. The memorial shown at right represents a proposal by John Colahan for a monument to Washington, detail shown in Figure 1.14 (The Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

George Bridport’s 1816 design led to two hundred years of various improvements, planting changes, and redesigns, but through that time, the core function and design of Washington Square has remained. Through all designs, Washington Square has maintained its diagonal walks, central feature, canopy trees, grass, and space for walking and sitting. Prominent designs from 1816 to 2022 are: George Bridport’s 1816 circular design, William F. Dixey’s 1881 geometric design, Olmsted Brother’s 1913 rotated design, Edwin Brumbaugh & Thomas Sears 1953 memorial & fountain design, and Fairmount Park Commission & Delta Group 1990s renovations. Presently, Washington Square maintains most design features from Brumbaugh’s 1953 design and various elements of each design since 1816.

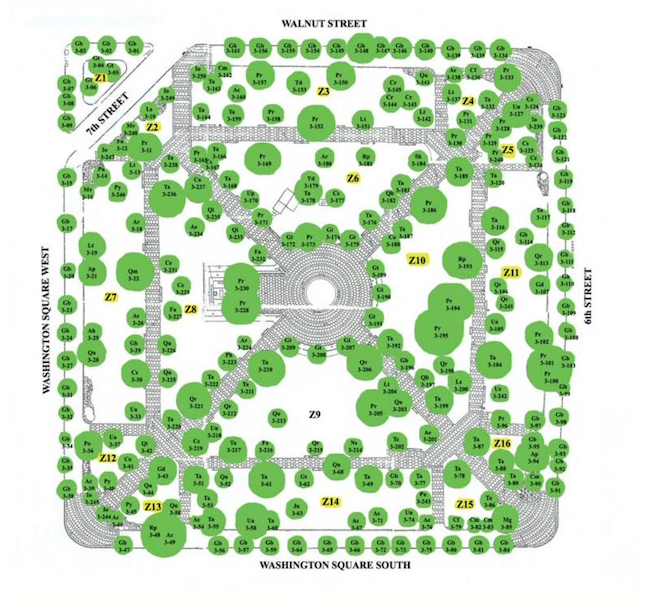

Figure 4: A Condition Assessment of Trees from 2007 that shows present day path design that was designed by Brumbaugh in 1953. (2007, Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation).

Even in this quick overview, the history of Washington Square is visible culturally, as a fabric of Philadelphia, and has been subject to designs by substantial designers and architects. In the Cultural Landscape Report for Washington Square (2010), the history and designs were extensively researched to determine what exactly makes Washington Square significant. In my report this summer, I will be updating the conditions of each element of the square and working to ensure Washington Square remains a cultural resource for future generations.

Figure 5: A group of people enjoying the lawn space in Washington Square (2022, INDE).

Interested in conservation efforts and want to learn about American Conservation Experience? If so, click here to view our programs, including our Conservation Crew and Emerging Professionals in Conservation (EPIC) programs. Click here to view conservation project locations across the United States.