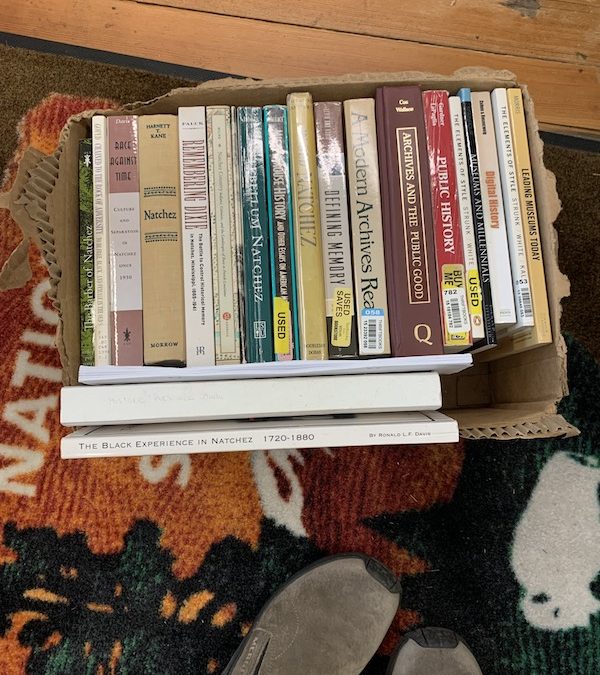

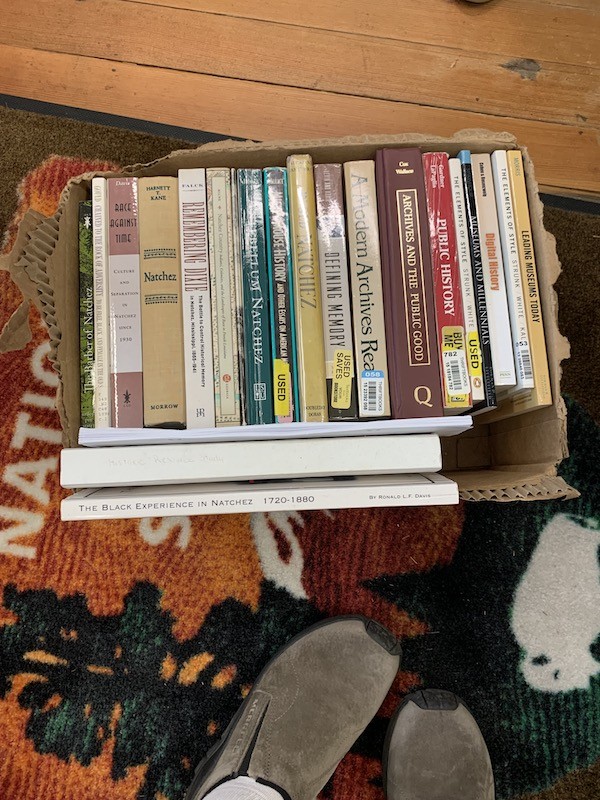

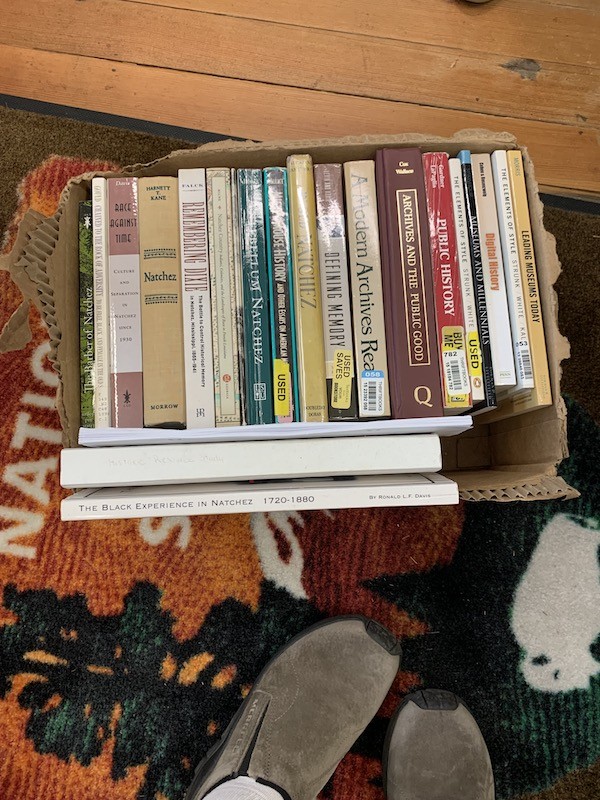

Box of Books on Natchez History

Written by: Gabrielle McFarland

When I accepted a position as a Historical Research Assistant for Natchez National Historical Park (NATC), I was aware of the extensive reading that awaited me but ultimately clueless as to where I should start or how to tackle it within the following eleven weeks. The NATC sites and their corresponding periods of interpretation stretch from the early eighteenth century (1716) through the Antebellum Period (1812–1861) alone. Beyond NATC, a thorough knowledge of the city of Natchez, Mississippi and its storied relationship with public history is required to contextualize when and how certain narratives were raised and either accepted or challenged.

Originally tasked with helping NATC build a research collection from a local community member’s archives, the allotted reading period was far from what I initially thought I needed to understand a historical collection and translate it into a finding aid. Upon arriving to the Lower Mississippi Delta, I felt thrown and overwhelmed by spaces that seemingly touched every major period of American history. I drew up a preliminary historiography of the area as an attempt to ground myself, but watched as the park library, interpretation team, and local recommendations shaped, shifted, and extended my list. After two short weeks I had a book, site, and stakeholder list for every period of habitation in Natchez.

A box of recommended readings.

As an inductive field of study, history is a waiting game. Reading leads to readings and question to questions. A juror on my thesis defense recently reassured me that it’s almost acceptable, even expected, for a historian to spend years on a topic without presentable findings. Grasping the simplest, chronological history of the park would take weeks, maybe months if I wanted to master the scope of our assignment.

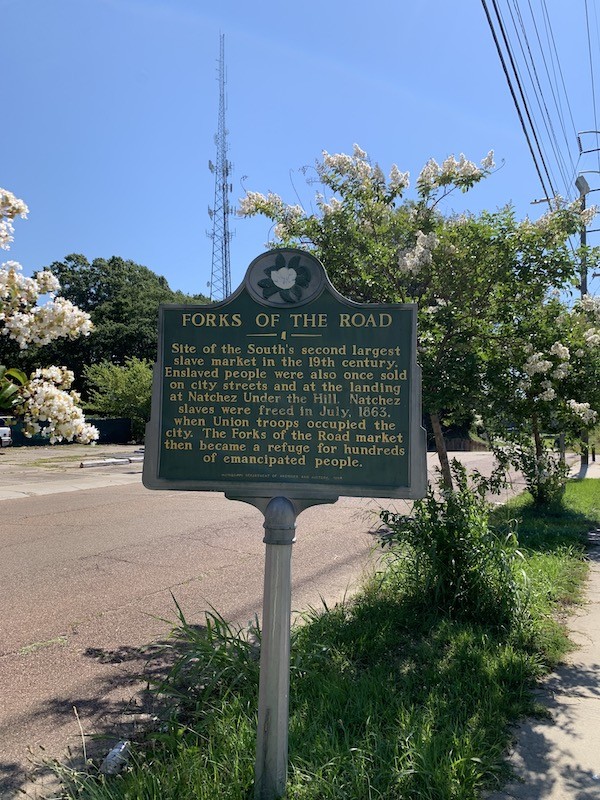

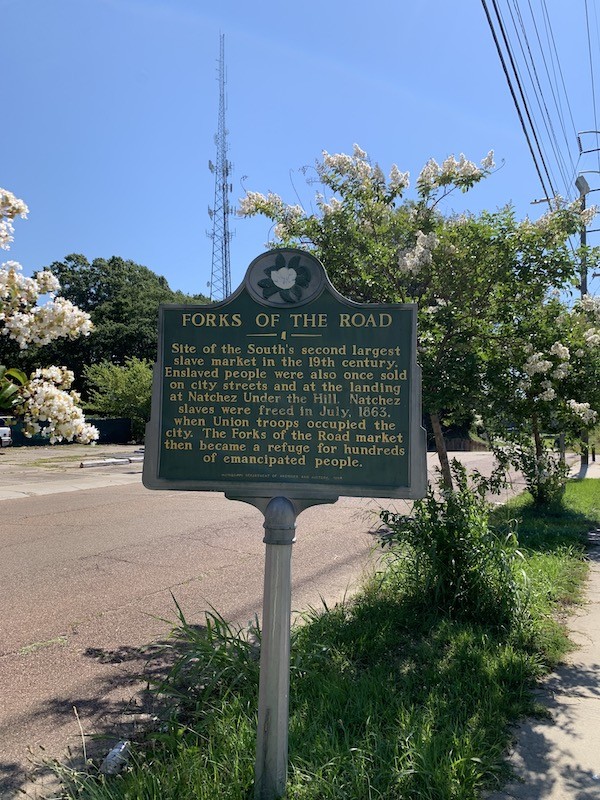

The research collection of interest aims to preserve knowledge surrounding the community research and public history efforts behind the creation of Forks of the Road as an NATC site. The most recent park addition sits at the former location of a slave market that was central to the American domestic slave trade (1808–1860, roughly). Unfortunately, after performing several Job Hazard Analyses (JHA), potential rat spoor contamination of the paper put the project on hold until proper safety measures can be met. Health risks may pose an existential threat to our project, but the past couple of weeks spent talking through paper conservation processes have been incredibly insightful, all the while providing extra time to catch up on essential readings and piece together the historical significance of Natchez and NATC.

Signage leading to Forks of the Road.

The human history of Natchez National Historical Park (NATC) began with the Nachee or Natchez Indians, who lived along the Mississippi River until killing, enslavement, and displacement campaigns experienced during the French settlement of the area forcibly removed them from ancestral lands in the 1730s (See Compagnie des Indes). Fort Rosalie, the former French fort that served as a site of rule, trade, and aggression between the French and Natchez, was established in 1716 and serves as one of the NATC sites today. The property changed hands from French rule onto British and later Spanish control before the organization of Mississippi Territory in 1798.

The grounds at Fort Rosalie, Natchez National Historical Park facing the Mississippi River.

The grounds at Fort Rosalie, Natchez National Historical Park facing southeast.

Natchez’s development history and incidental location along the river, coupled with the economic growth of the Cotton Belt, attracted further commerce to the area. NATC sites Melrose, William Johnson House, and Forks of the Road speak to the profitability witnessed in Natchez throughout the Antebellum Era (1812–1861). As I continue to familiarize myself with the existing literature behind the NATC sites, I’m actively seeking a point of entry to explore and analyze an issue beyond narrative history. Maybe this will begin with the safe processing of the research collection. Maybe not. Only time will tell.

Interested in learning more about American Conservation Experience, including our programs – Conservation Crew and Emerging Professionals in Conservation? If so, click here to check out our resources, media, and to apply online.