How to Interpret, In One Easy Step

Written By: Michaela Wang

Growing up at the National Parks throughout the American Midwest and Southeast, I absorbed a very idealized image of a park ranger: tall, clad in a quintessential ranger hat and pinecone belt, scaling snow-covered peaks and sustaining themselves off of hand-picked berries. So when I pulled up to the office in suburban Virginia, a couple miles down the road from a college town and a few minutes from a pizzeria, this image began to shatter. The rugged, internet-less cabin I envisioned was replaced by a simple office space––one you could find at a corporate office park. I was surprised to quickly befriend many young members, who were all working long-term and short-term positions like me. At our potluck, I watched law enforcement officers fire up hamburgers and hotdogs; our park superintendent sat down with us at the member table. In the next few weeks, my understanding of the National Park Service and my place in it deepened.

I think every new NPS member undergoes an unofficial, unspoken but collectively-felt course called National Park 101. My first big learning curve was understanding the park and its position in Virginia’s historical tourism industry as well as the broader national park landscape. Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail (CAJO) is not your average national park. Tracing the voyages of Captain John Smith throughout the Chesapeake Bay, the water-based trail spans across Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, DC, Pennsylvania, and New York. Our headquarters lie in Historic Jamestown but we operate through various visitor centers, museums, refuges, and parks along our length. So we really represent a cocktail of federal, state, and non-profit organizations, all working together to teach the history and ecology of the Bay.

Visiting one of our waysides at York River State Park in Williamsburg, VA.

In addition to a packed introduction to the National Park system, these past few weeks have also felt like Interpretation 101. I was surprised to find that there was no formal Virginia history or interpretation course I had to complete. No test to pass. My learning process has largely been hands-on, especially since the summer season here is packed with outreach events around the state. Only several chapters into my history books, I already began interpreting.

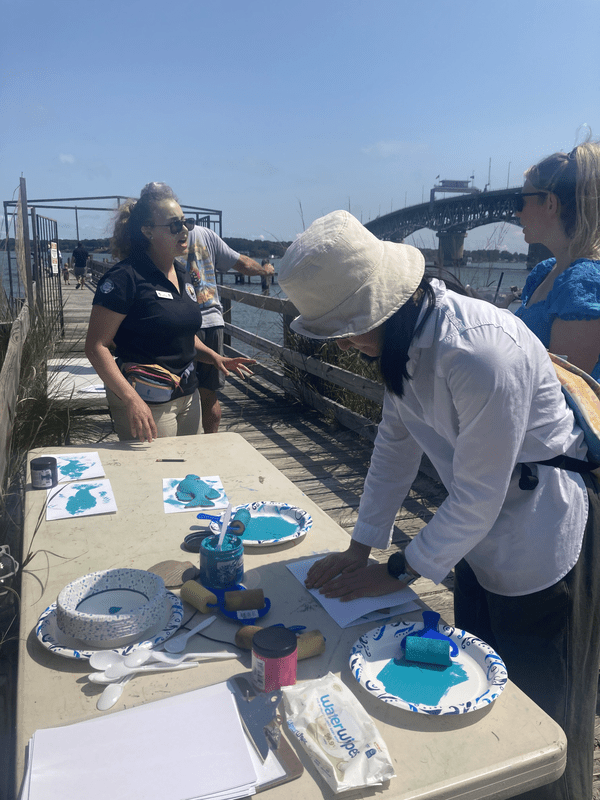

My first event was Virginia Free Fishing Weekend, set up on the dock of Yorktown Beach. I taught children how to do traditional Japanese fish prints and discussed indigenous fishing tools, while my coworkers ran the fishing station at the end of the dock. I demonstrated the design and use of indigenous nets, weirs, and spears, while also engaging the public in creating some fishing tools––resulting in a community net (see below). That day, I messed up my words and learned that a white shirt, though cooling, was a horrible choice in the presence of children and paint. Nevertheless, helping youth and adults understand bridge connections between history and their own lives felt energizing. Each interaction fueled the next; the only way to learn interpretation is to practice.

Demonstrating the making of a traditional fish net.

Assisting with fish printing.

The next weekend, we drove the Roving Ranger––our food truck turned interpretive booth on wheels––down to Military Appreciation Weekend in Yorktown. We explained 17th century European navigational tools (I never thought I would master a traverse board let alone come close to one) while promoting free national park passes to Veterans––all backdropped by the festival’s collision of sounds, from sea shanties to fife and drums to cannon balls.

Hotdogs? No, but we have cool badges.

Modeling a European navigational instrument.

This past weekend, several of us drove up to the Mattaponi reservation to attend their annual Powwow. We operated a touch table with furs, jewelry, and other material culture. Instead of spewing information, I instead posed questions to visitors, asking them what natural resources they thought the various pieces came from. Children’s faces lit up as they learned the thick fur came from a beaver, that the small basket was made out of the same pine needles in their backyard, or that pearl necklaces were once used as a form of currency. They were doubly excited when I signed their junior ranger booklets and handed them their badge. When interpretation becomes an exchange between interpreter and interpretee, it deconstructs authoritarian learning dynamics and helps foster deeper connections between the material and the visitor’s own life––what interpretation is all about.

Material culture booth at the Mattaponi Powwow.

Beyond interpretive events, I’ve also visited various sites relevant to my work. I not only got a tour of the Jamestown Settlement, our office backyard, but also visited Werowocomoco, the only piece of land that CAJO manages since 2016. The seat of power of the Powhatan chiefdom, as well as the meeting place between John Smith and Powhatan (and, most popularly-known, Pocahontas), the political and spiritual site carries spiritual and political significance for many Virginia Indians today. Later this summer, I will help create interpretive material for this site.

Rounding out my understanding of National Parks has also allowed me to see myself more in this space. National Parks are made for everyone, and, as a result, park interpreters need to reflect that diversity. In the next few months, I strive to lean into the challenges of interpretation and curriculum development, process external feedback, and ultimately create quality educational products that reach wide audiences.