Piecing the Past

Written by: Loissa Harrison-Parks

Hello everyone!

I have now entered the 4th week of my internship at Gateway National Recreation Area! Lots of exciting things have been going on now that the dust has settled and I am fully acclimated into the position.

These past couple weeks have been primarily focused on cataloguing and site excavation, however, I’ve also begun generating various source material/media for the archeological portion of Gateway’s website.

As stated in my previous blog, Gateway comprises 3 main parks: Fort Wadsworth in Staten Island, Jamaica Bay in Queens and Sandy Hook in New Jersey. My office is located at headquarters in Fort Wadsworth. This is where the majority of the artifacts are stored.

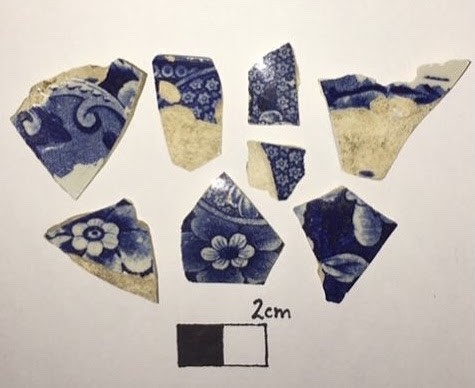

Artifacts range from personal items such as: buttons, smoking pipes, glass bottles, and stoneware, to military items and building materials. Once discovered, they are collected by archeologists, labeled, then placed in archive boxes until they’re ready to be catalogued.

Since starting my internship, I’ve catalogued over 150 artifacts. About 99% of artifacts are fragmented or incomplete. This is largely due to the objects being buried for over 100 years but ecological and human factors also have an effect.

While excavating the Sandy Hook site, we’ve found a plethora of the artifacts listed above. Nails, bricks and ceramic fragments are among the most frequent, followed by glass sherds (better known as beach glass).

The Sandy Hook site has been an amazing opportunity to refresh my archeological skills.

Our project began with a general site survey, followed by digging a few test pits. These test pits, which are usually no larger than 3’ x 3’, provided an idea of where the parameters of the site. If the test pits contain artifacts, then we can include its area within the parameters of the excavation. If the pit yields no artifacts, then it’s safe to say that particular area should not be included in the excavation.

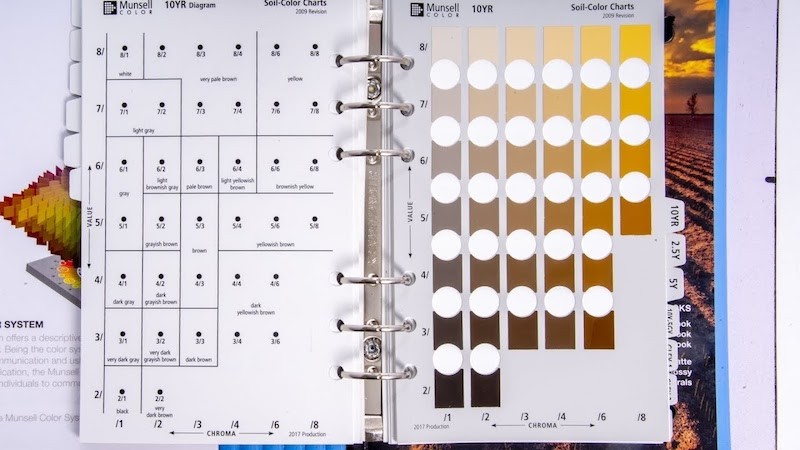

After discovering the parameters of the site, we set a grid and began stratigraphic excavations of each block within the grid. Stratigraphic excavation removes and analyzes each individual soil level as they are encountered. Each layer of soil is then identified using a Munsell Soil Identification Book.

This was the first full week of site excavation and my first time partaking in a dig located so close to the coastline. One of the first things I learned was how to identify top soil. From there, I learned to identify different layers of sand and analyze how brick, metal, heat and vegetation may affect its characteristics.

For instance, evidence of the fire that destroyed the site almost 150 years ago can be seen through charcoal fragments, burnt building materials and ash that remains buried within the soil. I also learned that when sandstone and brick reach high temperature, they (much like ash) can stain the sand. Everything I learn is synthesized as I work towards creating new Gateway interpretation materials.

Now that I have a well-rounded understanding of Gateway’s archeological data, I can begin the process of creating content for park visitors. Spending time between the field and the park’s museum collection has given me a new insight into artifacts and their relationship with their environment.

I’ve found that the creation of new interpretive material starts with a little introspective either at the excavation site or when handling artifacts during the cataloging process. Sure, context is supremely important when conducting digs but I try to put myself into the shoes of someone less familiar with the park.

*Just a quick disclaimer: Any civilian who unintentionally stumbles onto an archeological site or artifact should immediately contact a park official.*

A good example would be a situation I found myself in just a few days ago. While site surveying the beach, I stumbled upon a pile of burned glass. (Disregarding all of the information I knew about the site and it’s fire in 1859) I examined the artifact. I knew the object was burned because glass, changes color, loses transparency and warps after reaching high temperatures.

From there, I analyzed my surroundings, or geological environment. If there is burned glass, then there should be evidence of the fire itself; burned sand or charcoal for instance. If there isn’t, then I must ask myself why that is. How did burned glass end up in an area with no signs of fire damage?

Again, without using any background knowledge of the site, I can see that the glass must have been moved into its current location. Perhaps, due to its coastline location, it was washed away from its initial location due to a storm. Or maybe, looters were digging around and left it. All of these hypotheses are a valid way to open dialogue around artifacts. This is the type of problem solving/thinking that must be presented to the public. Not only in regards to tangible artifacts, but to the park and its history.

Now that the analytical process has been explained, the next step is to contemplate how artifacts fit into a larger historical narrative and how to present that narrative to the public. Luckily, the National Park Service has tons of information available regarding how to interpret information to the public. The first and perhaps the most important step is to familiarize myself with said material. Brochures, handouts and park archeology websites are a great way to start.

Right now, I’m creating an outline for a brochure that will include a timeline of the park’s archeological history. The timeline will have images of common artifacts in relation to their period. I am excited to be a part of such a unique and creative way to enhance the public’s understanding of Gateway’s history.