Week 6 – Deliberating rights: Constitutional Conventions and the Disenfranchised

by: Michelle Dempsey

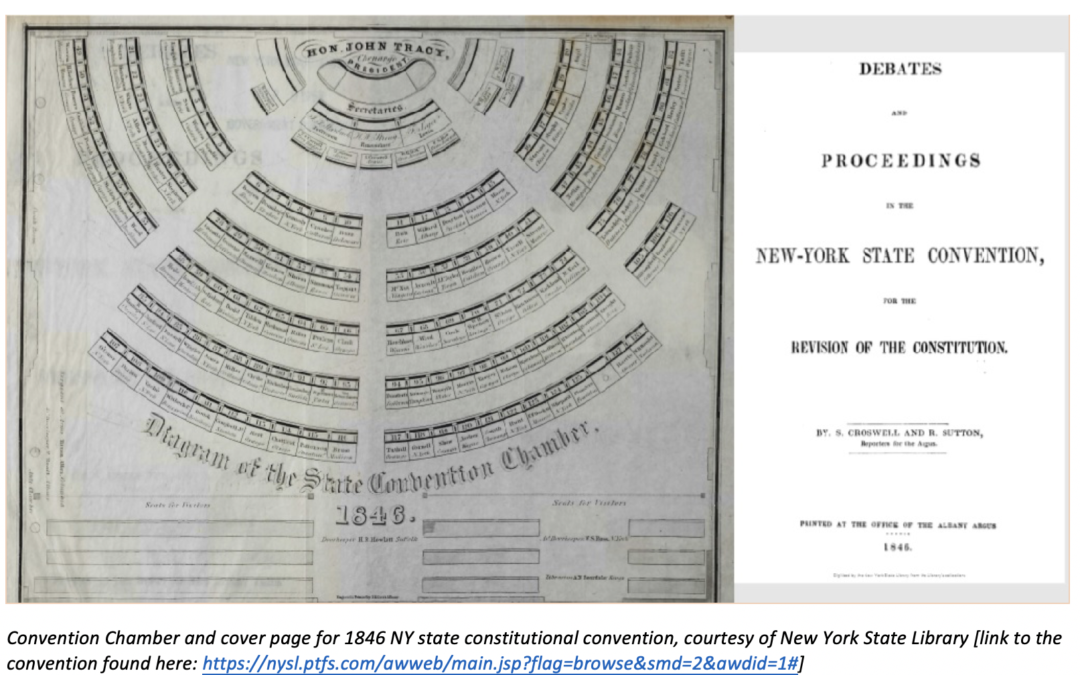

The past couple weeks have been mostly made up of primary research on voting rights in New York. I finished reading through over 900 pages of the 1821 New York State Constitutional Convention (hooray!) and moved on to finish the 1846 convention, which also hovered around 900 pages. Many of the arguments from 1821 again resurfaced in 1846. Should property be necessary as a voting requirement? Should African Americans be entitled to equal privileges as white citizens? While the 1821 convention eliminated most property requirements for white male citizens, black men were still required to possess 250 dollars in order to vote (as I had noted in my previous blog post). The 1846 Convention, edging ever nearer to the upcoming sectional crisis, made concerns about class and race prominent. Some representatives, such as Isaac Burr, believed that “they [the men of the 1821 convention] made a retrograde movement – that they took a step toward the dark ages” and asked, “should this Convention in 1846, take still another step in that direction, by continuing this odious provision, and by disenfranchising another portion of our tax-paying native born citizens?” However, the majority of the men at the convention agreed that the status of African Americans was not, and should not be, equal to white men, and the property requirement remained.

The past couple weeks have been mostly made up of primary research on voting rights in New York. I finished reading through over 900 pages of the 1821 New York State Constitutional Convention (hooray!) and moved on to finish the 1846 convention, which also hovered around 900 pages. Many of the arguments from 1821 again resurfaced in 1846. Should property be necessary as a voting requirement? Should African Americans be entitled to equal privileges as white citizens? While the 1821 convention eliminated most property requirements for white male citizens, black men were still required to possess 250 dollars in order to vote (as I had noted in my previous blog post). The 1846 Convention, edging ever nearer to the upcoming sectional crisis, made concerns about class and race prominent. Some representatives, such as Isaac Burr, believed that “they [the men of the 1821 convention] made a retrograde movement – that they took a step toward the dark ages” and asked, “should this Convention in 1846, take still another step in that direction, by continuing this odious provision, and by disenfranchising another portion of our tax-paying native born citizens?” However, the majority of the men at the convention agreed that the status of African Americans was not, and should not be, equal to white men, and the property requirement remained.

At this convention, the roles and rights of another group of Americans were brought up for discussion: women. In the first couple days of the convention, trouble apparently arose due to men taking up the front row of the women’s gallery, the designated space for women to observe the proceedings of the convention. After a petition was presented on behalf of the women by John Leslie Russell, an argument ensued about how to handle the situation. Some men believed that a few doorkeepers should be placed in order to properly reserve the ladies’ seats because, as Russell noted, “The high consideration in which the sex were held in this country, and should be everywhere, demanded that the privileges which they did enjoy should be fully secured to them.” While many were in favor of protecting the ladies’ gallery in some way, by means of doorkeepers or signs, Benjamin Bruce commented that “he was somewhat suspicious of this new-born zeal of certain gentlemen, veteran members of the legislature, on behalf of the ladies.” Russell made the point that the previous two sessions had appointed doorkeepers, and the delegates resolved to maintain one doorkeeper for the ladies’ gallery for the remainder of the convention. I found this passage particularly interesting, as it highlights the growing role and interest American women were taking in politics as the nineteenth century moved forward. The maintaining a gallery for women, even though still separate from men, meant that women were encouraged to be engaged in politics not only for the sake of their brothers, fathers, and husbands, with whom they were meant to converse and socialize with, but also for their own sake, as men were meant to protect the interests of the women under their care.

At this convention, the roles and rights of another group of Americans were brought up for discussion: women. In the first couple days of the convention, trouble apparently arose due to men taking up the front row of the women’s gallery, the designated space for women to observe the proceedings of the convention. After a petition was presented on behalf of the women by John Leslie Russell, an argument ensued about how to handle the situation. Some men believed that a few doorkeepers should be placed in order to properly reserve the ladies’ seats because, as Russell noted, “The high consideration in which the sex were held in this country, and should be everywhere, demanded that the privileges which they did enjoy should be fully secured to them.” While many were in favor of protecting the ladies’ gallery in some way, by means of doorkeepers or signs, Benjamin Bruce commented that “he was somewhat suspicious of this new-born zeal of certain gentlemen, veteran members of the legislature, on behalf of the ladies.” Russell made the point that the previous two sessions had appointed doorkeepers, and the delegates resolved to maintain one doorkeeper for the ladies’ gallery for the remainder of the convention. I found this passage particularly interesting, as it highlights the growing role and interest American women were taking in politics as the nineteenth century moved forward. The maintaining a gallery for women, even though still separate from men, meant that women were encouraged to be engaged in politics not only for the sake of their brothers, fathers, and husbands, with whom they were meant to converse and socialize with, but also for their own sake, as men were meant to protect the interests of the women under their care.

The question of women’s rights continued as the convention progressed, this time concerning the property rights of married women. The 1846 convention proceedings reveal a great concern on this topic on behalf of the men present. A proposal was introduced which stated that “All property of the wife owned by her at the time of her marriage and that acquired by her afterwards by gift, devise, or descent or otherwise than from her husband, shall be her separate property.” This proposal meant giving to married women a right they previously did not have under the law: the right to their own property. This issue was contested hotly, and some men noted that “this subject had been before the legislature for many years, and if there was any desire among the people for such a provision, they should have known it.” He went on to note that “this separation of interest and division of property between man and wife, would produce domestic trouble.” However, many others noted that this provision would mean women were protected from profligate husbands, sons, and other male relatives destined to inherit the property women brought to their marriage or obtained after. In the end, the provision passed; however, it was only slowly and sporadically enforced over the ensuing years.

As noted by historian Lori Ginzberg, several petitions by women made their way to the 1846 convention (through their county representatives), which not only asked for married women’s property rights, but also their right to vote. Two years before the momentous Seneca Falls women’s rights convention in 1848, a group of six women from Jefferson County asked of the convention to “extend to women equal, and civil and political rights with men,” invoking the Declaration of Independence as they proclaimed equality of men and women “a self-evident truth” which “is sufficiently plain without argument” (Ginzberg 4). While at least two other women’s petitions made it to the convention, the records were apparently lost in the 1911 Capitol Building fire. Prior to Seneca Falls, women across the state of New York publicly desired to expand the rights promised to them, as citizens, under the founding documents of the United States. The debates about property, voting, rights, privileges, and citizenship which permeated both the 1821 and 1846 constitutional conventions made the problem of women’s citizenship paramount in the years to come, as Americans increasingly pondered which rights women should have. As Ginzberg notes, these women petitioners, and the men they petitioned, knew that “the right to hold property, so long associated with independent citizenship, would alter women’s status as citizens” (Ginzberg 144). The results of the 1846 convention meant that married women could now be considered property holders. If property-holding black men could vote, why not women?