GREENWAYS – IF YOU CAN DIG IT, DO IT!

Honest disclosure: if I could redesign a city, every street would become a park.

If there is one thing I learned during my time thus far in Boston, is that Bostonians love their parks. And that is no surprise; between Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace, the historic Boston Commons, and the Greenway, there is no shortage of urban oasis in Boston!

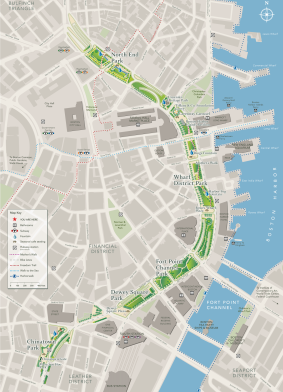

I have always found the Greenway particularly interesting; the project bridges between urban rejuvenation and cultural restoration. I had the absolute pleasure this week to meet Keelin Caldwell, an Associate Director of Programs with the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy, and join her on a tour of the Greenway to learn a little bit more about its history and its future. We began the tour in Chinatown and made our way north, stopping here and there to admire sites and cool off in the shade. Many of the facts that Keelin shared with us surprised me: the Greenway hosts over 400 events each year and that it has been instrumental in the revival of food trucks in the city. Compared to other park projects in the last few decades, the Greenway leads the way using a 50-50 funding model between public and non-profit sources. The R.F.K. Greenway oversees the development, maintenance, and governance of the Greenway, but the city supports the Conservancy. I love how the Greenway is designed to accommodate the needs of casual, spontaneous use. Little things, like moveable furniture, are often avoided in parks because of the risk of misuse or theft; however, the furniture on the Greenway allows visitors to create their own experience of the place. Keelin also talked about how since the Greenway opened, it has been coined the happiest place in Boston. I totally agree. The Greenway hosts an impressive collection of horticultural variety; I was taken back by how well many of the large trees and plantings were adapted to a human-environment. Unlike a traditional park, the Greenway’s plants root into a highly engineered ground, because it sits above the tunnel.

The Greenway from above. Source: Wikimedia.

The Greenway’s history did not start so ‘green.’ In fact, it was anything but. Before the linear park existed, the 3.5 miles long swath of the city was divided by an elevated highway (Interstate-93) that was constructed around the 1950s. Similar to many infrastructure projects of that period, cities sought highway project to alleviate road congestion, gentrify older districts, and divide city neighborhoods. When constructed through Boston, Interstate-93 cut through buildings, broke entire neighborhoods from the city downtown, and reconstructed the social space of the city – unfortunately for the worse.

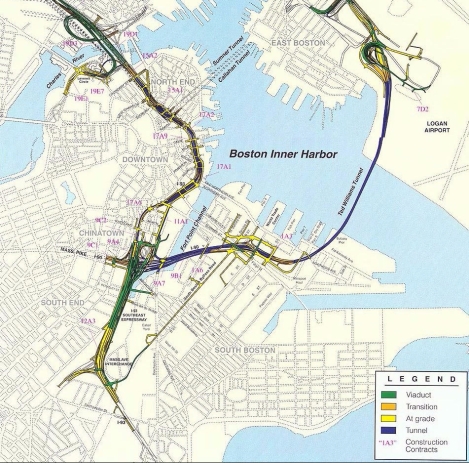

In 1982, a project began to revisit the existence of the elevated highway. The city chose an ambitious project: to put the highway underground. The Central Artery/Tunnel Project was the first of its kind, at least at its scale (and budget). In 1991, ground finally broke and the construction started; it lasted 16 long years. During the construction period, a call for proposals was released, to envision a new use for the restored land. The Conservancy, various architects and landscape architects, planners, and engineers collaborated together to compose a new park for the city of Boston. The design incorporated public art, social spaces, transportation connections, horticultural resources, cultural sites, play spaces, and venues, large and small. The many components of the park attach linearly above where the interstate traces underground. The park, as Keelin described, is a new type of park for Boston, because it focuses on ‘urban modern.’ Finally in 2006, Boston’s Greenway came to fruition.

Big Dig planning. Source: Mass DOT

My interests in landscape architecture tend to focus around infrastructure and transportation. I believe streets and rails to be some of the most persistent construction in out landscapes and cities. They structure the development of cities, support the lives of millions of people over hundreds of years, and are often hardly given second glance. The Big Dig contrasts many of these emphases. At first, it was a highway aligned independent of Boston’s existing transportation network, and divided city life, rather than connect it. The Greenway gave the people back that portion of the city, but in many ways it is a complete reinvention upon a scar that will never truly heal. The highway incision was a city surgery gone wrong, but I think the Greenway exemplifies urban social resilience.

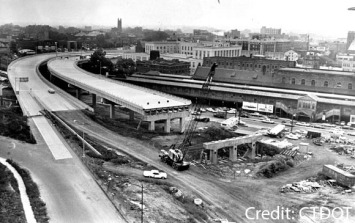

Learning about the Greenway reminded me of a project (currently underway) in my home city of Hartford, Connecticut. In the 1950s, Interstate-84 was constructed through the central core of the city. Similar to Interstate-93 in Boston, the elevated highway divided downtown from the northern districts, demolished entire ethnic neighborhoods, and turned the breadth of Hartford into a giant parking lot. Over the past half-century, the viaduct has aged, pressing Hartford to plan reconstruction.

View of Hartford during the last few months of construction. Interstate-84 runs east-west through the city, narrowly avoiding Bushnell Park, the State Capitol, and Union Station. Source: Hartford Preservation Alliance

The Interstate-84 Project began to study different options for the highway and sought public input. I often dream about Hartford undertaking their own Big Dig project, reconnecting Downtown, and spurring a renaissance of city life. After following the project’s progress over the last few years, an Interstate-84 tunnel appears out of question and I fear a reverberation of tough times for Hartford.

Construction of the Interstate-84 viaduct, with historic Union Station in the background. Source: CT DOT

So, how does this relate to landscape preservation? Everything!

Although, infrastructure projects of this scale often leave complete physical destruction in their path, they create a space to reconnect parts of the city previously severed. Landscape preservation is just as much about social memories and character of the environment, as it is about perpetuating existing elements. When you walk along the Greenway in Boston, you walk through dozens of neighborhoods simultaneously. The Greenway’s design expresses the culture and history of the city in subtle ways. Although, I would have to see more historical narrative sewn into the design, I think that Bostonians already recognize the park as part of their own histories.