Rain, Rain Go Away

by: Mariah Walzer

Let’s start with the bad news. The site I was supposed to help excavate this summer is down this path:

That’s right. It’s underwater. It’s been raining for the past week, and the forecast calls for even more rain this week. But as a teacher of mine pointed out, this is all just part of being an archaeologist. Sometimes your site floods, sometimes you have to evacuate due to fires, and sometimes your site gets destroyed by ISIS (true story for one of the PhD students I met at University of Chicago). You get pretty good at rolling with the punches.

Now, on to the good news: I picked up another project! Remember all those projectile points I identified from that donated collection? At the end of my last post, I had just started creating an educational presentation using the artifacts. Well, with all this indoors time, I completed one presentation on archaeology at Monocacy National Battlefield in general, and I am finishing up another on lithic technology and analysis.

(Pop quiz! What does “lithic” mean? See the end of my post for the answer.)

One of my first slides tackles some common misconceptions about archaeology, especially the infamous dinosaur comments. (No, archaeologists do not study dinosaurs.)

I really enjoyed this project, because archaeology education is one of my passions. History can seem boring and feel very distant from us, if not taught well. Archaeology has a special opportunity to bring history to life because of its focus on artifacts, tangible pieces of the past.

Here’s a quick story to illustrate. On my first field school, we visited Kettle Falls, Washington, which used to be a major salmon fishery before the Grand Coulee Dam permanently flooded the Falls and stopped the salmon from swimming up river. On the bluff above the river, there is a very large sharpening stone that was moved to preserve it shortly before the dam became operational. I ran my fingers along the many grooves in that rock. It was amazing to think that my hands could touch the same rock that other people touched potentially thousands of years ago. It was a very powerful moment for me. I always think about that stone when I consider the power of artifacts to make a connection between the past and the present.

Grooves worn into the stone from years and years of indigenous people sharpening their spears and other tools here.

Looking through other CRDIP-ers’ posts, I noticed a theme echoing around: telling untold stories. I also emphasize this theme in my presentation, because I believe it is one of the most important goals of archaeology. Written history is only part of the story, set down by those with the means and ability to write. It often ignores the voices of the illiterate, the “losers,” and those who live(d) in cultures focused on oral tradition. Archaeology gives us opportunities to give those people a voice, retroactively at least.

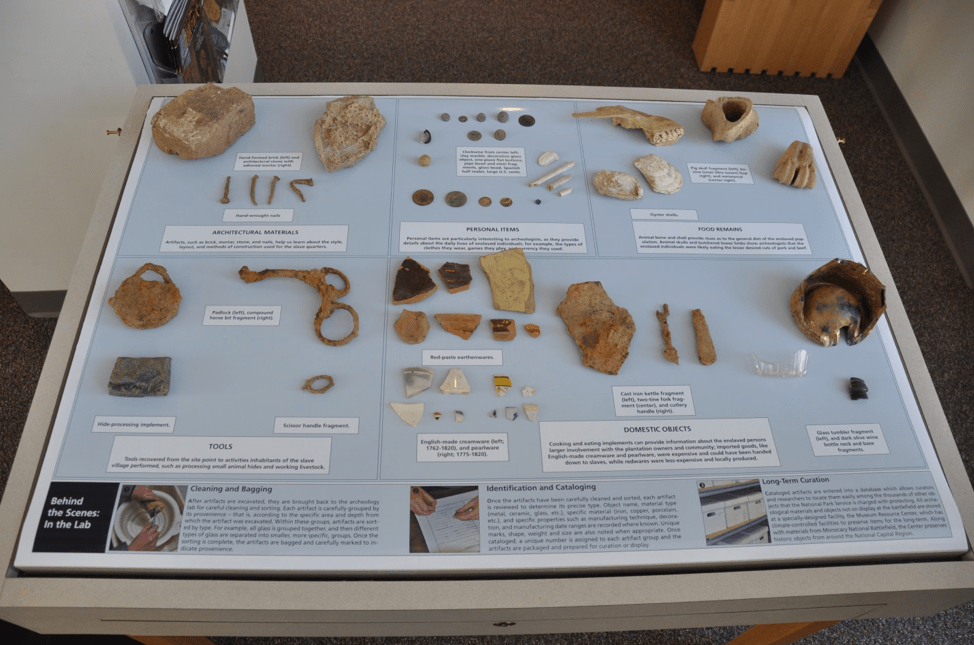

At Monocacy NB, excavations in 2010 – 2012 sought to learn about a group of people that we know little about: enslaved persons in Maryland. The area currently known as Best Farm was called L’Hermitage from 1794 to 1827, when it was owned by the Vincendières, French plantation owner refugees from Saint Domingue (now Haiti). The Vincendières were the second largest slaveholders in Frederick, Maryland, with somewhere between 50 and 90 enslaved persons at their maximum. Survey in 2004 discovered the approximate location of slave quarters that were mentioned in historical documents. The 2010-2012 excavations sought to learn about the structure of the houses and the organization of the village, as well as uncover any artifacts related to the slaves’ lives. Six nearly identical structures were found and many artifacts. This project offered the chance to tell another of the many stories that played out on park land. After all, the Civil War was only four years and the Battle of Monocacy one day, yet people have been living in this area for over 10,000 years.

Photo from Monocacy NB’s exhibit on the L’Hermitage Slave Village. Artifacts such as coins, pottery and glass pieces, pipe stems, and the handle of a pair of scissors give us a glimpse into the lives of the enslaved persons at L’Hermitage.

3D reconstruction of the L’Hermitage Slave Village from Monocacy NB. The six slave houses (bottom right) were very uniformly placed and constructed, showcasing the heavy restrictions placed on the enslaved persons. The overseer may have lived in the white and stone house closest to the center, and the Vincendière family would have lived in the main house (the all-white building in the top left).

I gave a test run of my presentation to the Youth Conservation Corps kids working at the park this summer. Then, on one of the few sunny days we’ve had, the YCC joined us to dig some shovel test pits for a project to move a fence to better reflect its probable location at the time of the war. The high schoolers told me that they really enjoyed their Archaeology Day, so mission accomplished!

I’m looking forward to presenting to the public at Infantry Day on August 11th! It’s hard to believe I have less than two weeks left here, though. Time flies so fast when you’re having fun!

Pop quiz answer: “Lithic” means stone. When archaeologists talk about lithic technology, or “lithics” for short, we’re referring to stone tools like projectile points and groundstone (mortar & pestle, axes, hammerstones, etc.)