Wrapping up, but full speed ahead

Week 10

by: Michelle Dempsey

Over the last couple weeks, I have largely been pulling together the research I have conducted over the past several months.

I have almost finished putting together the biographies necessary for our voting rights activity for fifth graders. Each student will receive a historical person, and the interpreters will be asking students various questions about who is able to vote during what time. I have created a timeline of key dates and events for students, so they can place their person in the appropriate historical context. The goal is to get students to think about what voting looks like when only a small number out of the population is able to vote.

![]() With the education staff, we have come up with a list of 25 people, some more well known than others, who represent various demographics in American society through the 20th century. We have chosen men and women of different socioeconomic statuses, time periods, and races, and each student will randomly choose a historical character to learn about. Most of these people relate in some way to the state of New York. However, we realized that several crucial moments (and people) involved in voting rights history for the U.S. operated outside the realm of this state, especially concerning Native Americans and citizenship. While the Onondaga nation made their opposition to the 1924 Snyder Act (also known as the Indian Citizenship Act) known, we decided to include a Native American man named John Elk from Nebraska who sued for his right to vote in 1883. We have also decided to include Zitkala-Sa, one of the most prolific Native American authors and activists of the 20th century, who fought for Native American and women’s suffrage until the end of her life.

With the education staff, we have come up with a list of 25 people, some more well known than others, who represent various demographics in American society through the 20th century. We have chosen men and women of different socioeconomic statuses, time periods, and races, and each student will randomly choose a historical character to learn about. Most of these people relate in some way to the state of New York. However, we realized that several crucial moments (and people) involved in voting rights history for the U.S. operated outside the realm of this state, especially concerning Native Americans and citizenship. While the Onondaga nation made their opposition to the 1924 Snyder Act (also known as the Indian Citizenship Act) known, we decided to include a Native American man named John Elk from Nebraska who sued for his right to vote in 1883. We have also decided to include Zitkala-Sa, one of the most prolific Native American authors and activists of the 20th century, who fought for Native American and women’s suffrage until the end of her life.

One of the most time-consuming, but important, aspects of this project is including as much information as possible about people history has barely remembered. Rather than simply having a bio card for a “poor white man” or “free black man” in the 19th century, I have been digging, with the help of the staff here at Lindenwald, to find names and stories about people who did not leave much historical evidence behind. For example, we are including two slaves who had passed time at Lindenwald. George was enslaved by the well-known Van Ness family of Kinderhook, who owned the home before Martin Van Buren. George sought his freedom in 1804, which we know from a runaway ad that the students will be able to read for themselves. We have also included Levi, a slave belonging to Henry Clay. Levi is a person interpreted at Lindenwald, for the guest bedroom on the first floor, known as the best bedroom, is set up to resemble Henry Clay’s visit to Lindenwald in 1849. Levi had become truant twice in his life, but he returned both times for reasons unknown. We are hoping to show through these stories that, as enslaved persons, Levi and George had no rights to American citizenship. After the 1857 Dred Scott Case, this status included all African Americans even though increasing numbers of propertied African American men were able to vote leading up to the Civil War.

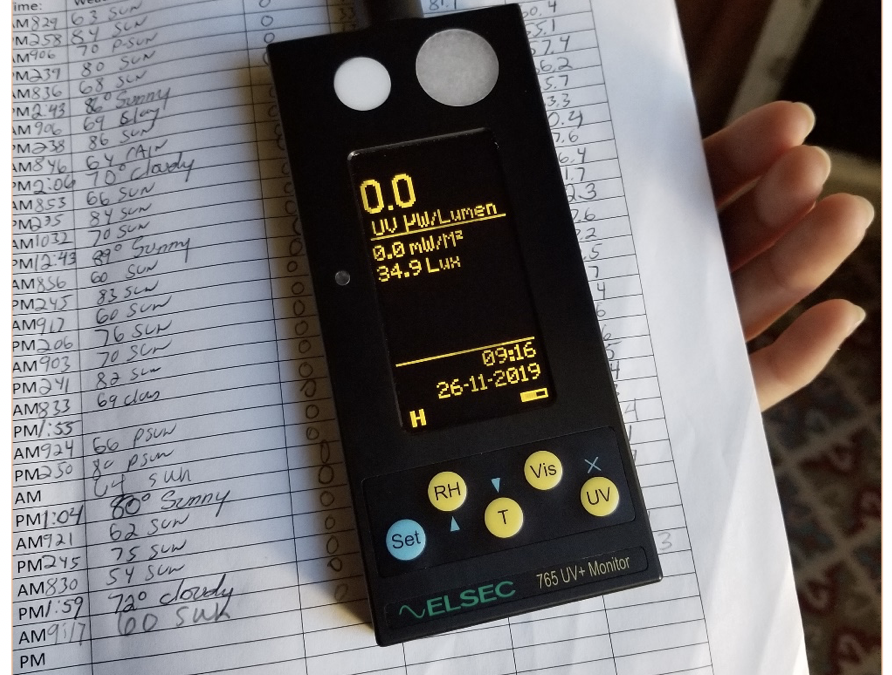

In between conducting research and finalizing my projects here at Lindenwald, I have also been assisting the curatorial staff around the house. I have been assisting in the ins and outs of light monitoring, Integrated Pest Management, and general handling and caretaking of objects and collections. The following photos show the light reader used to monitor and track the UV light, visible light, temperature, and relative humidity in the many rooms around the house. The more information that is collected, the better the curatorial staff can care for the objects in the house. For instance, UV shades have been installed in most rooms to protect furniture and textiles from harmful light. Tracking which bugs have managed to find their way into the house can reveal if moisture levels are changing. Dusting, sweeping, and vacuuming all help keep objects clean and pest levels down.